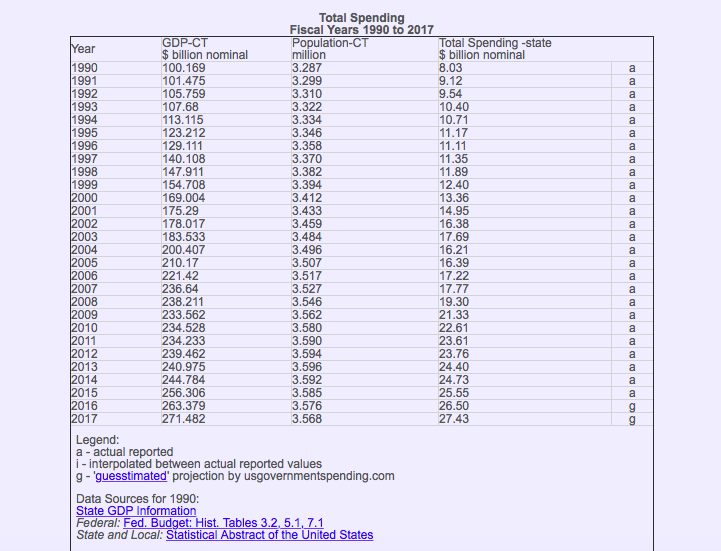

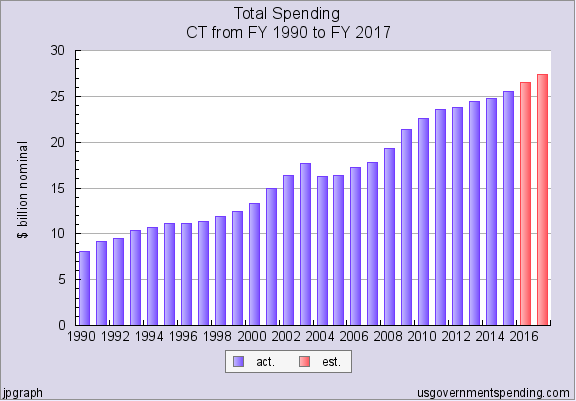

Connecticut’s government spending outpaced the state’s gross domestic product by a wide margin since 1990, according to a review of past figures compiled at U.S. Government Spending, an online database of state and federal spending.

In 1990, just before the implementation of the state income tax, Connecticut’s total spending topped $8 billion for the year, which amounted to $2,436 for each of Connecticut’s 3.2 million residents at the time. The state’s GDP was $100.1 billion per year.

In 2017, Connecticut’s total spending amounted to $27.43 billion, or $7,687 per resident, and the state’s GDP was $271.4 billion.

Controlling for inflation, Connecticut’s state spending grew 87 percent since 1990, whereas the GDP which supports the state grew a mere 48 percent. The state’s population only grew by 300,000 residents during that 27 year period.

Connecticut raised taxes a number of times during the 27 intervening years, notably the implementation of the state income tax, and major tax increases in 2003, 2009, 2011 and 2015 to deal with budget deficits.

A 2016 study of the state income tax found that between 1991 and 2014, Connecticut took in $126 billion in state income taxes. During that time, spending on debt service, pensions and employee healthcare benefits grew 174 percent over inflation.

The two other biggest areas of government spending growth were the Department of Correction, which grew 103 percent, and welfare programs, which grew 70 percent, according to the study.

The subsequent tax increases, including raising the top marginal state income tax rate from 4.5 percent to 6.99 percent, has done little to stave off rising costs and budget deficits, which came to a head this past year as the state faced down a daunting $5.1 billion deficit.

Lawmakers were mostly able to avoid major tax increases, and proposals to raise the state sales tax, the top marginal income tax, a cell phone tax and a tax on second homes were pushed aside.

Part of the deficit was closed through a $1.5 billion concessions agreement with state employee unions, but the effects of the concessions deal may haunt future budget negotiations as it guarantees wage increases and layoff protections for state employees and extends the life of the benefits contract until 2027.

The new budget signed by the governor on Tuesday did raise some taxes and fees, but was largely able to balance the budget on cuts to municipal aid coupled with reforms to state mandates on municipalities to help offset the cuts.

Adding to the tax burden is the fact that Connecticut’s population has only grown by 300,000 residents in 27 years.

The high cost of living in Connecticut combined with slow economic growth has led to people moving to other states. Connecticut’s population has steadily declined over the past four years, while income tax revenue has leveled off, and, in some cases, fallen short of expectations.

Despite passage of a new budget, the state may face high hurdles during the next budget-writing session as lawmakers will have to grapple with state employee pay raises outlined in the SEBAC concessions deal and rising fixed costs related to pensions, retiree healthcare and debt service.

The Office of Fiscal Analysis projects Connecticut will face a $4.6 billion deficit in 2020 and 2021.