The American and Filipino troops could not withstand Japan’s relentless assault on the Bataan Peninsula — located in Luzon, Philippines — any longer. Ammunition, food and medicine were low. The casualties mounted, and reinforcement was impossible.

From Dec. 8, 1941, into the early months of 1942, the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) valiantly fought and even stalled the Japan’s advance to control Manila Bay, despite lacking air support — for the Japanese had destroyed more than half of the United States’ bombers and fighters only hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Yet Japan re-strengthened its force in March, while the USAFFE could not. The situation turned more dire when, on orders from U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Gen. Douglas MacArthur (commander of the U.S. and Filipino forces) evacuated to Australia on March 11. He famously pledged to return, but his promise would take years to fulfill.

The Japanese invasion was too overwhelming. On April 9, 1942, the U.S. and Filipino forces surrendered Bataan, and more than 76,000 men became prisoners of war (POW). The horrors were only beginning.

The POWs were forced to endure a hellish 65-mile trek from the Bataan Peninsula, known as the Death March, to be transported to prison camps. The Japanese inflicted savage cruelty, as stated by The National WWII Museum:

“The prisoners of war were forced to march through tropical conditions, enduring heat, humidity, and rain without adequate medical care. They suffered from starvation, having to sleep in the harsh conditions of the Philippines. The prisoners unable to make it through the march were beaten, killed, and sometimes beheaded.”

The captors even “made sport of hurting or killing the POWs,” and forced prisoners to receive sun treatment: making “them sit in the sweltering heat of the direct sun for hours at a time without shade,” according to the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

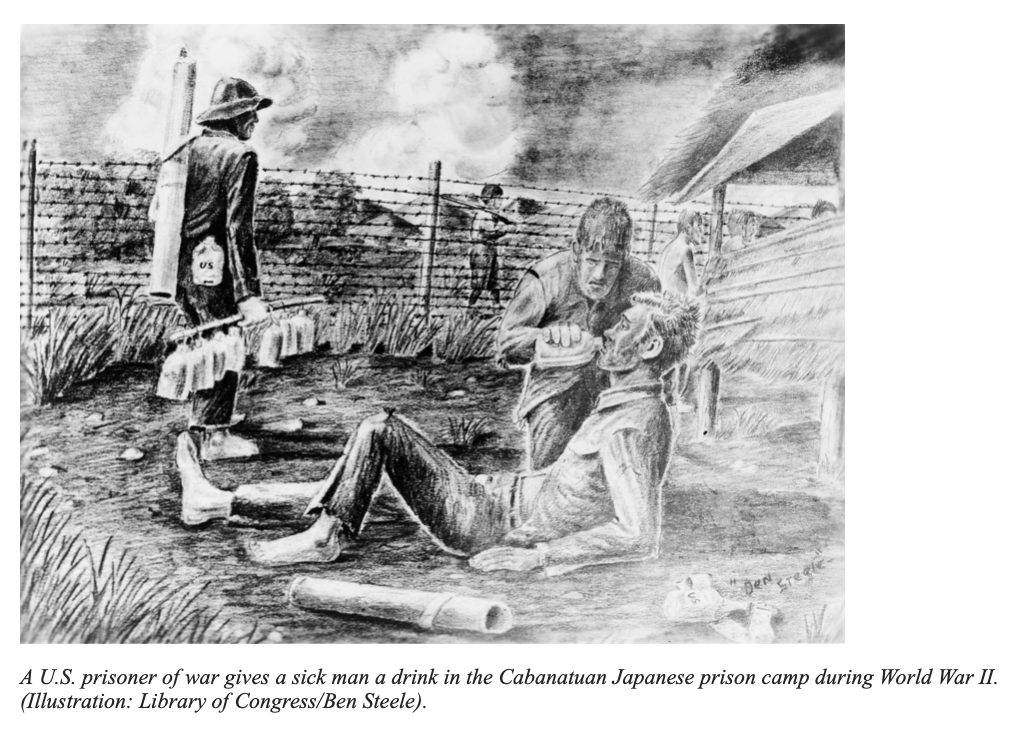

More than 11,000 prisoners died in the Death March. The ones who survived fared little better in captivity, as 40 percent of American prisoners perished from malnutrition and abuse throughout the war’s duration. Only a few escaped, who shared “chilling accounts of widespread Japanese atrocities” to the American public. Outraged, the public demanded swift action for the safe return of the POWs, like the 500 Americans who toiled at a camp near Cabanatuan.

On Jan. 30, 1945, the prayers — of both Americans at home and in the camp — were answered. This is the story of what has become known as “The Great Raid,” and the Connecticut man who led hundreds to freedom.

‘Too Short’

Henry Mucci, the future leader of “The Great Raid,” was born in 1909 to Sicilian emigrees in Bridgeport. He lived at 247 Sixth Street, attending Lincoln School and then Warren Harding High School (where he was selected best looking and most popular in his class, according to the Italian American Connecticut newspaper, La Sentinella).

The Muccis were a large family, and many of Henry’s “brothers also served in the Army and Navy during the Second World War, while his sisters worked at the VFW in America and made bazookas in factories,” as noted in his Air Rangers in the Sky (ARITS) biography.

A patriotic young man, Mucci applied to West Point in November 1930. Although he placed first in the competitive examination, he was rejected as “short” in the physical portion. Nevertheless, the Bridgeport native persisted in pursuing a military career and building his strength, joining the Connecticut National Guard. In January 1932, he was designated by President Herbert Hoover to re-take the West Point entrance exam, which he successfully did in March that year. While at the military academy, Mucci remained active, participating on the equestrian and lacrosse teams and training in hand-to-hand combat like boxing and judo. He eventually graduated in May 1936, receiving his “diploma and commission as second lieutenant from Gen. John J. Pershing who was attending the 50th reunion of his own West Point class,” according to La Sentinella (Oct. 25, 1946).

Between his graduation and the United States’ entry into World War II, Mucci bounced from Randolph Field, Texas and Fort Francis in Warren, Wyo. to Schofield Barracks on Oahu, Hawaii — 16 miles away from Pearl Harbor. In fact, Mucci survived the Japanese sneak attack on Dec. 7, 1941, that killed more than 3,000 U.S. soldiers. Although not a primary target, the barracks did sustain machine gun fire, while “[s]oldiers stationed at the barracks took to the roof to fire back with rifles, though they were largely unsuccessful,” as stated by Pearl Harbor’s official website.

A few years later, in February 1943, Mucci was assigned by the U.S. Sixth Army to lead the 98th Field Artillery Battalion, which had become an obsolete mule-drawn pack unit. Most of the men, known as “mule skinners,” were “boys from the farms and ranches of middle America,” according to the Public Broadcasting Station (PBS). But the new commanding officer was a “man of vision” — or perhaps a little crazy, as his soldiers attested. For more than a year, the unit trained in “torturous exercises across the tropical New Guinea jungles, through treacherous rivers, and up mountainsides in the ferocious heat.” As one soldier, John Richardson, remembered:

“I thought he was going to kill us. He called us rats, he called us everything but a child of God. And he told us, ‘I’m going to make you so d—– mean, you will kill your own grandmother.’…I wondered why he was putting us through so much, but before it was over, there was no question about it, I knew why. And once he got us trained and picked out, he loved us to death. And there wasn’t anything too good for us. …He knew what he was doing when he was training us.”

By the end of 1944, he transformed the group into the Sixth Ranger Battalion: an elite, commando force known as the Army Rangers.

The Raid

Under Mucci’s tutelage, the Army Rangers became one of the first American special operations fighting forces, ready for any mission assigned to them.

Then a mission came from Gen. Walter Krueger: as the United States successfully liberated islands from Japanese occupation, the Axis Power reportedly “intended to execute prisoners of war in response to the Allies’ advance,” according to Today In Connecticut History. The general believed Mucci and his men were up to the task of rescuing more than 500 American prisoners at the Cabanatuan camp. But his unit — comprised of 121 Army Rangers and 250 Filipino guerillas — had to act quickly. With time of the essence, Mucci developed a plan in 48 hours.

The camp was more than 30 miles behind enemy lines and encased in the jungle, and his men had to “crawl over or past the shallow graves of more than 2,500 prisoners,” according to Mucci’s New York Times obituary. Yet they successfully traversed the terrain, undetected. On Jan. 28, 1945, Mucci “secured guides, and moved to rendezvous with the Scouts, who reported that three thousand enemy, with some tanks, were in the stockade area” near the prison camp, as noted in a military citation. The Army Rangers were outgunned and outmanned (2 to 1) by the Japanese; regardless, Mucci set his trap on the road leading toward the prison camp and stockade. As reported by the Associated Press (AP):

“Mucci put his forces on either side of the stockade to blockade the road during the action. He deployed a larger force of Rangers near the road farther south and a force of guerrillas farther north. With these in position the rescue force crept from a river thicket onto a field making a direct approach to the prison just before 7 p.m. That was the darkest hour of the night.”

On Jan. 30, Mucci ordered the attack. Debate remains on how quickly the operation went, but within three to five minutes, the Army Rangers stormed the camp and neutralized the Japanese guards. Within ten minutes, Mucci and his unit freed the more-than-500 prisoners. But it was not over yet. There were “several thousand Japanese soldiers only a short distance away”; however, the Rangers evacuated the liberated Americans “without detection and at dawn reached Sidal where they were met by a motorized party,” as noted in the AP report. Soldiers recalled how Mucci tended to the men during the operation, striding “up and down the column all night spurring it on with, ‘All right men, just three kilometers more, just three more.’”

Despite the risky expedition, the Rangers suffered minor casualties compared to the 300 Japanese who were killed. For his daring-do efforts, Mucci received the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest U.S. military decoration.

‘The Dawn of My Return’

After the rescue mission, Mucci was treated as a national and international hero. Regarding the latter, on behalf of King George VI, Mucci was awarded the Distinguished Service Order by Lord Inverchapel, British Ambassador to the United States, in the presence of Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, according to La Sentinella (March 28, 1947).

Due to his newfound popularity (and recognizable cap and pipe), the Bridgeport native set his sights on a new endeavor: politics.

In 1946, the Democratic Party nominated him for the House of Representatives seat vacated by Clair Booth Luce. However, he faced John Davis Lodge — the eventual 79th Connecticut governor — and lost by 35,600 votes. The New York Times suggests Mucci could not recoup after a display of ‘one-up-manship’:

“[He] told how his mother had come to America from Italy with $16 in her pocket and said that he had not been born with a silver spoon in his mouth. Mr. Lodge, sensing an oblique attack on his Brahmin background, was gracious, praising Mr. Mucci as a great credit to Italian-Americans and all Americans and then delivering his own speech in Italian, a language Mr. Mucci did not speak. The coup was widely credited with winning the election for Mr. Lodge…”

After the failed campaign, the war hero “abandoned public life and eventually went to work as a Far Eastern representative of the Sunningdale Oil Company of Calgary, Alberta, living for many years in Singapore, commuting frequently to Saigon and dismissing rumors that he was working for the Central Intelligence Agency,” according to his New York Times obituary. As the obituary notes, however, Mucci was in Saigon until the day before the city fell, which further raised suspicions of his possible position.

After a long life, he passed away on April 20, 1997, at 88 years old.

Today, commuters and/or passersby traveling on Route 25 between Bridgeport and Newtown drive on the Col. Henry Mucci Highway, named in the hero’s honor. Even Hollywood memorialized Mucci’s tenacious actions in the 2005 film, “The Great Raid,” starring Benjamin Bratt as the Connecticut native.

For all the memorializing, the names of the 500 prisoners of war he rescued are not as well-known. Yet it is quite possible those veterans had children — and their children had children. Ultimately, Mucci and the Army Rangers did not save only 500 souls from torture and death during the raid on Jan. 30, 1945; they made possible the lives of the countless unborn generations thereafter.

His tenacity makes one contemplate the legacy of our own actions. And what greater legacy can one have?

Till next time —

Your Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Andy Fowler

William Michael Willert

January 30, 2024 @ 9:53 am

From 1943-1946, My father-William Albert Willert was in the U.S.Navy, and volunteered as a Frogman, and served in the Pacific; he was part of “the greatest generation”. He was wounded, has a purple heart and a bronz star. He survived until 2009, and passed away at age 45.

My brother & I display his medals, and tell his story to my grand children to this day, as we believe the story of that generation of young men should not ever be forgotten.

Thanks for your account of this “Great raid”.