SUMMARY

Governor Ned Lamont, on April 1, asked state lawmakers to ratify tentative agreements with 15 state government unions that negotiated under a single banner—the State Employee Bargaining Agent Coalition, or SEBAC. These unions represent the bulk of the state workforce. State senators and representatives in coming weeks will be asked to cast a single up-or-down vote on whether to bind state government to the terms, detailed in more than 1,700 pages, until 2025.

The agreements call for a pair of bonuses totaling $3,500 for full-time employees and up to two retroactive raises, to be followed by up to two raises each in July 2022 and July 2023. For some employee groups, salaries would climb 21 percent over the next 15 months. Recent retirees would have their pensions retroactively increased based on what their final pay would have been. Limited data shared by the Lamont administration show the deal would add well over $1 billion to state costs in the first 27 months alone.

Negotiations appear to have had no impact on state healthcare coverage or pension contributions, leaving untouched a benefit package that far exceeds what is commonly found in Connecticut’s private sector.

Besides amounting to an all-or-nothing ultimatum from the governor, there are several reasons the General Assembly should reject the deal:

- The agreements would cost far more than they appear. The estimates presented to lawmakers omitted information, in different instances, ranging from the effect of pay raises on employer payroll taxes and pension contributions to, in a dozen instances, any estimate of fiscal 2025 costs. More importantly, the agreements call for another round of pay negotiations beginning in 2024 which is not being considered in the present cost of the agreements. The deal would also increase the state’s unfunded pension liability.

- The terms would push the compensation enjoyed by state employees further beyond private-sector norms after state employees received four automatic pay increases over just 18 months between 2019 and 2021. This follows two decades in which the state payroll had grown significantly more than private-sector payrolls in the state. The agreements would leave unchanged healthcare and pension benefits that far exceed what is commonly found in the private-sector.

- Paying bonuses in the spring instead of July would squander an opportunity to mitigate a forecast wave of retirements ahead of changes to state retirement rules in early summer.

- The agreements would give labor unions new ways to intimidate state workers into paying them, among other things banning state managers from listening to union membership pitches and requiring agencies to print “scab lists” naming the people who choose not to become union members.

- Despite adding significantly to taxpayers costs, the contracts achieve little by way of reforming how state government operates.

The General Assembly should reject this deal, demand that future agreements come with a complete accounting of their costs and impact on pension obligations, and use legislation instead of collective bargaining to change things such as employee discipline rules and to block the payment of any bonuses before the state has passed the June 30 change in retirement rules.

BACKGROUND

Most of Connecticut’s state government workforce operates under rules set by union contracts.

These agreements control not only pay and benefits but also a wide range of terms and conditions of employment, from work hours to discipline processes to the price of dinner in a state office cafeteria.

Contract negotiations are conducted behind closed doors, with even state lawmakers – the people’s representatives — unaware of what’s being offered or demanded.

Beginning in 1975, the General Assembly adopted laws giving state employee unions some of the most powerful bargaining privileges in the country. Ultimately, union leaders gained the power to use binding arbitration to settle contracts, negotiate pension benefits, and develop contract terms that supersede state laws, among other measures.

The effect of this outsized influence over government decision-making became particularly visible to residents in 1991, when state unions refused to make concessions to mend a massive budget gap unless Governor Lowell Weicker sought creation of a personal income tax. In the years since, government unions have repeatedly pressured the General Assembly to hike tax rates to finance more raises and more hiring.

Besides affecting the state’s bottom line, union contracts make agency operations more inflexible.

When consultants last year released findings from a state-funded project to “evaluate workforce efficiency and organizational design,” they repeatedly cited the effect of the state’s collective-bargaining rules on state service delivery. For instance, the report authors noted:

“…the process of removing a low-performing employee from a role is complex and can take years. Several managers indicated that they instead look for ways to minimize the impact of a low performer or find a way to move them onto another team.”i

For most state employees, the union contracts covering their position expired in June 2021. (Some judicial branch workers’ contracts, which were included in the negotiations, will expire in June 2022).

Negotiations for successor agreements present an opportunity to legislatively change the least favorable terms in the just-expired contracts, or to take the issues off the table entirely without fear of litigation for contract impairment.

Talks with the unions began in earnest last year, with multiple state agencies negotiating with the unions that represent their own employees. UConn leadership, for example, negotiated with the four units containing UConn faculty and other workers.

Governor Lamont’s office on March 8 announced a tentative agreement, encompassing about three dozen individual contracts, had been reached that would run through June 2025.

The agreement, his statement said, “honors the state’s fiscal priorities through positive and productive negotiations with representatives of our state’s dedicated workforce.”ii

Lamont’s statement said he would “respect” the ratification process. Contract terms and cost estimates were withheld from the public (and their elected officials in the General Assembly) until union members had voted to approve them.

The administration stallediii Freedom of Information Act requests to view the tentative agreements while union members were still voting, but finally released the terms, albeit with missing sections and incomplete cost estimates, on April 1.

Under state law, the General Assembly must vote on whether to ratify the deal. The General Assembly’s nonpartisan Office of Fiscal Analysis will issue a fiscal note that helps lawmakers better understand the added cost of the agreement.

MAJOR PROVISIONS

The tentative agreement uses the just-expired (or soon-to-expire) contracts of each of the 15 unions as a baseline.

In some cases, there are minor changes such as allowing paperwork to be filed electronically instead of mailed.

There are three noteworthy areas in which changes were made—or not.

BONUSES & RAISES

With the exception of a small group of workers whose contracts have not yet expired, the agreement calls for the following pay increases:

- $2,500 “special lump sum payment” (bonus) for full-time employees, prorated for part-timers and payable immediately after ratification;

- 2.5 percent general wage increase (GWI), retroactive to July 1, 2021;

- Immediate “increment” or similar seniority-based unit-specific increase, which generally average 2 percent, retroactive to July 1, 2021; (for employees at the top of their position’s pay scale, increments involve a lump sum rather than a rate increase)

- $1,000 bonus for full-time employees, prorated for part-timers, payable in July 2022;

- 2.5 percent GWI and additional increment or similar increase in July 2022; and

- 2.5 percent GWI and additional increment or similar increase in July 2023.

In each of the above cases, the additional pay would be “pensionable”—that is, each employee’s pension would be based on the higher amounts received. The deal also calls for retroactive pension increases for people who retired between July 1, 2021 and the date of ratification, with pensions being recalculated as though the retiree received the higher pay in their final months.

Looking solely at the general wage increases and assuming a 2-percent increment, the agreement would call for a state employee (belonging to the pension system) making the 2020 average pay ($74,297) to receive about $2,500 in back pay on top of the $3,500 in bonus payments.

The agreement would also make smaller, agency-specific changes to starting pay rates, holiday pay, overtime, and other pay rules.

Governor Lamont has said higher salaries are necessary to fill certain positions, and the agreements in some cases modify the starting pay for certain state workers (such as engineers at the Department of Transportation).iv In other cases, the state is offering special overtime rates to employees who now work a “full-time” 35-hour work week to encourage them to instead work 40 hours.

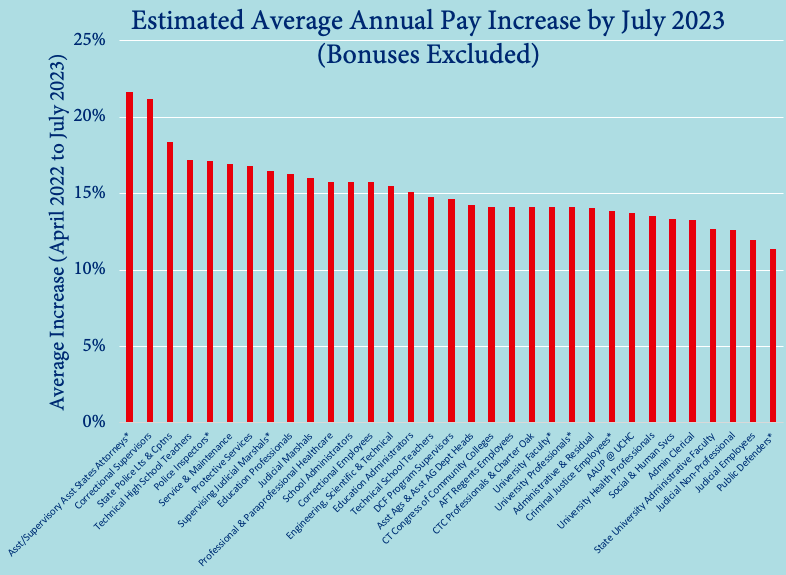

The 37 cost estimates presented to the General Assembly in some cases cover multiple bargaining units, while other estimates appear to cover different portions within a single unit. All told, 33 of the 37 groups are poised to get raises averaging 15.2 percent (unweighted) between now and July 2023. (Some judiciary employee contracts have not yet expired, and their wage increases are treated separately). (Figure 1)

For two groups–assistant and supervisor assistant state’s attorneys and correctional supervisors—the raises will average more than 20 percent over just 15 months.

Figure 1.

The agreement notably would not increase wages during the final year of the deal (July 2024 to June 2025), which will make it appear less costly. Instead, the state would be committed to renegotiating pay (and pay alone) after January 2024—a provision known as a “reopener.”

BENEFITS

Another notable omission in the agreement is what it would not change.

The healthcare and pension benefits for the unions are covered by a separate 10-year contract last negotiated in 2017. The unions and state negotiator had the option to modify its main terms in parallel with these contract talks, but elected not to.

This means the bonuses, backpay, and raises come while the state leaves intact a complement of benefits that increasingly exceeds private-sector norms (see below).

The only change in the benefit arena was the launch of Prudent Rx, a voluntary prescription drug savings program, which state and union officials say will save $30 million per year by reducing drug costs for the roughly 132,000 employees and dependents covered by the state plan (as well as pre-Medicare retirees).

DISCIPLINE

On the non-monetary side, the deal makes modest changes to employee discipline rules for some bargaining units, allowing the state to dismiss employees found, two years in a row, to have “unsatisfactory” performance.v

The state has generally struggled to terminate employees. In a one-year period ending February 2019, the state terminated 76 permanent employees (people who had completed their probationary period) out of a pool of roughly 30,000 workers.vi

It’s not clear how many employees would match the new criteria.

Absent anything from senior state officials defending particular “gets” in the agreement, this appears to be the most notable improvement for management over the just-expired deals.

WHY IT SHOULD BE REJECTED

The General Assembly has the final say over whether this agreement receives the imprimatur of law. State representatives and senators have historically been willing to reject labor agreements that failed to adequately take the public interest into account; in 1994 alone, five deals crafted by arbitrators were rejected.vii

In this case, there are five key reasons to say “no” and send negotiators back to the table.

THE COST WOULD BE HIGHER THAN STATED

Rudimentary cost estimates released on April 1 show the deal, if ratified, would easily add more than $1 billion to state costs during the first 27 months. These initial estimates, however, did not apply a standard formula or present future costs in a uniform format.

In some cases, no cost information was presented. In others, the cost estimates omitted the effect on employer payroll taxes such as Medicare and Social Security or pension contributions.

Estimates also omitted basic information such as the number of employees affected. In other cases, estimates did not include the added costs in the final year of the deal (FY2025).

A more detailed analysis, using internal state agency data, will be generated in coming weeks by the General Assembly’s nonpartisan Office of Fiscal Analysis.

The OFA analysis will likely address issues such as the failure by some agencies to consider fringe costs and to present fiscal 2025 costs.

OFA analysts are skilled professionals. Their review, however, will be limited to the specific terms submitted.

The agreements appear designed to conceal a major piece of their Year 4 costs by including “reopener” language. This means the state would be committed to negotiating again in 2024 about pay rates as of July 1, 2024.

On paper, this would not add to costs. But given the state’s arbitration rules (and previous state pay agreements), it is unlikely that pay would not rise in fiscal 2025.

As SEBAC said in its literature to promote ratification, the reopener means “it will be renegotiated. It does not mean a 0% or no steps.”viii

This makes the deal appear less expensive, since the alternative would be to allow the contracts themselves to expire at the end of June 2024 instead of June 2025.

OFA is also unlikely to consider the effects on the State Employees Retirement System (SERS) from the retroactive pension increases or spiking the final average salaries of soon-to-retire workers with pensionable bonuses.

Both SEBAC and Governor Lamont have meanwhile indicated that the unions will continue seeking “pandemic pay” for days worked over the past two years.

“The issue of hazard or pandemic pay was not part of these negotiations and will be resolved as part of another agreement,” Lamont said.ix

SEBAC, on the other hand, told its members that “contract negotiations purposefully did not include pandemic pay conversations. SEBAC is fighting for this in different venues.”

These “different venues,” which SEBAC also calls a “two-track fight,” involve pressing for pandemic pay through collective bargaining or arbitration. Meanwhile, unions are trying to end-run the bargaining process by having the General Assembly award it legislatively.

The failure to explicitly settle the pandemic pay question, and the continued public statements to the contrary, means the General Assembly could approve the deal only to face the separate cost of an arbitration award or some other secret negotiation.

Between the Year 4 raises and pandemic pay, the final cost of the agreement could be understated by hundreds of millions of dollars under the OFA analysis.

Meanwhile, the state is again using claimed “savings” to conceal the actual costs of a labor deal and smooth its passage through the General Assembly.

The $30 million annual savings—from the voluntary Prudent Rx drug program—may not fully materialize, causing the net cost of the deal to rise.

Looking specifically at prescription drugs, the Malloy administration in 2017 said it expected to save $110 million over four years by adopting the CVS standard formulary for prescription drugs, but saved only $81 million.x A smaller drug “savings” push was ultimately scrapped in fiscal 2020 after cost reductions came in below a quarter of forecast levels.

The bonuses and raises come with another undetermined cost: they will increase pressure on the General Assembly and state agencies to increase pay rates for managerial and other non-union state employees.

THE DEAL DOES NOT REFLECT CONNECTICUT’S ECONOMIC REALITY

The proposed deal comes after unionized state employees received four raises over 18 months.

Workers received across-the-board raises of 3.5 percent in July 2019, followed by increments—seniority-based raises (or lump sums)—in January 2020. Despite the state’s tenuous fiscal position in the early months of the pandemic, another round of 3.5 percent raises automatically went through in July 2020. And another round of increments kicked in at the start of 2021. Generally speaking, these raises totaled about 11 percent during one of the most difficult economic periods in state history.

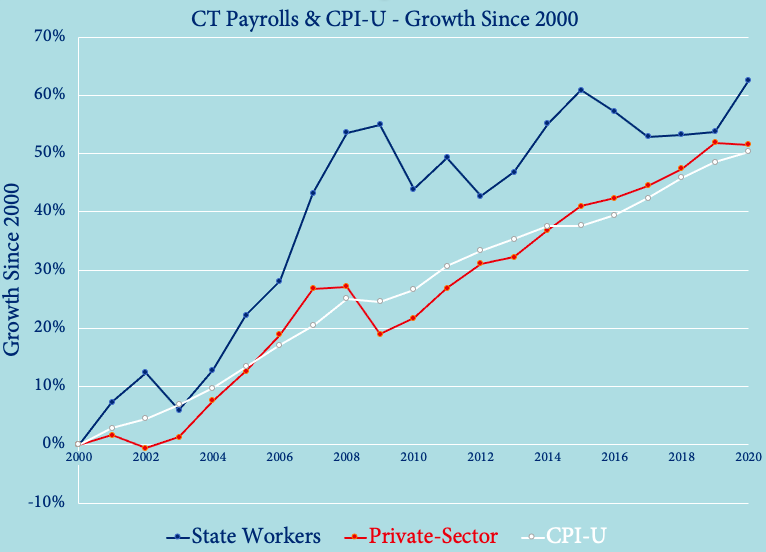

Since 2000, the state payroll, as measured by federal economic officials, has climbed faster than both inflation and Connecticut’s private-sector payrolls—that is, the people largely responsible for financing state government (Figure 2).

Page Break

Figure 2

Ideally, the cost of the workforce would generally track the wage growth in the private sector. Instead, in each year since 2000, the total payroll has been larger than it would have been had its growth mirrored that of the private-sector—due to both the number of people working for the state and what they were paid.

In the aggregate, the Connecticut’s state government payroll (as measured by the QCEW) totaled $9.6 billion more (2022 dollars) between 2000 and 2020 than it would have if the payroll had grown at the rate of inflation.

This, of course, is an incomplete analysis: it does not capture the value of employee benefits—or the value of multi-year guarantees that shielded state workers from layoffs until mid-2021.

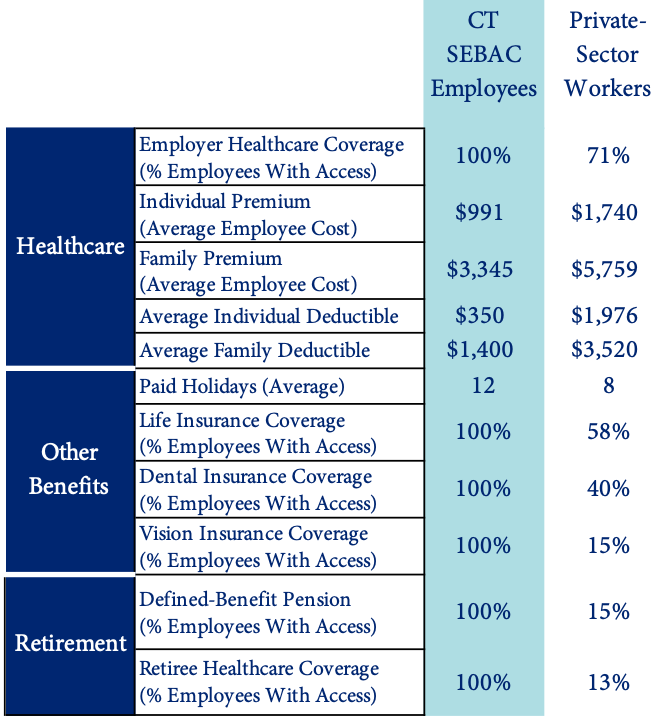

State employees enjoy healthcare, retirement, and paid time-off rules that have increasingly exceeded private-sector norms, as shown in Table 1 below:

Table 1. SEBAC and Private-Sector Benefits, Compared

Here labor has presented two contradictory arguments. On the one hand, union officials have described years without general wage increases—when they were shielded from layoffs and benefits were preserved—as “sacrifice.” But they have separately defended the benefits package as something for which they “traded,” pointing back to the years of “sacrifice.”xi

Even accepting the premise that state pay should continue rising as quickly as the state can afford, state revenues are forecast to grow 2.7 percent or less in fiscal 2024, 2025 and 2026.xii

This deal, as crafted, would put considerable pressure on other state programs, straining the state’s ability to fund key priorities—either in terms of new spending or tax relief.

IT WOULD NOT ADDRESS THE RETIREMENT WAVE

The agreement represents a missed opportunity for the state to manage an expected wave of retirements ahead of a scheduled change to state pension benefits this summer.

Pension agreements negotiated in 2011 and 2017 created an incentive for eligible workers to retire by June 30, 2022. After that, future pension cost of living adjustments and retiree healthcare benefits will be less generous. As of April 1, state government had already had more retirements than it did in all of 2020, according to reporting by the CT Mirror.xiii

But under the tentative agreements, just $1,000 of the $3,500 bonus would be reserved for employees who stay on past the June 30 cliff. What’s more, the bonus would be pensionable, meaning it would increase pension payments (and the state’s pension liability). This would compound on the also-pensionable backpay that the tentative agreement would award to people who retired as early as nine months ago.

Faced with such a serious incentive challenge, the state should not be issuing a “special lump sum payment” to workers on their way out the door when that same money could be used to encourage them to continue working if paid just months later.

IT TIGHTENS LABOR’S STRANGLEHOLD ON STATE GOVERNMENT

Labor unions in 2018 lost their power to force state workers to pay them, and the share of union-represented workers electing to continue paying has declined.

The unions have turned to the state’s elected officials—many of whom won office with labor’s backing—for ways to boost their rolls. Last year the General Assembly passed a bill that gives public-sector unions new powers to pressure people to join.xiv Among other things, it requires state agencies to share the home addresses of all new employees.

These agreements would go to even greater extremes to help labor reverse its losses by granting new, extraordinary privileges—while exposing state taxpayers to costly federal litigation.

For one thing, it would force managers to leave the room during union orientation sessions, when new employees are pressured to join. This is a reckless move because, as the fiscal agent for the unions, state government will be held liable if a dispute arises about the terms and conditions of union membership.

What’s more, as a general practice, state managers should be present to ensure that union officials aren’t using illegal coercive methods to pressure workers to join.

The agreement would compel state agencies to print what amount to “scab lists” for every union, making it easier to target the people who chose not to pay dues the prior month.

It would also bar the state from collecting dues for other professional associations that workers may choose to join. This move, which likely amounts to unlawful viewpoint discrimination, could also land the state in federal court if an association, or even another labor union, were to sue.

THE PUBLIC WOULD GET LITTLE IN RETURN

Governor Lamont, who has indicated he wants to “respect” the ratification process, has not spoken publicly about the state getting anything in return for the generous pay provisions and preserved benefit levels in the deal.

It is possible that seemingly minor changes present a meaningful improvement for management that is not yet being fully appreciated. But state negotiators appear to have won little in return for the generous bonus and wage terms.

Connecticut has a bad track record of letting the General Assembly and governor’s prerogative get weakened by the collective bargaining process.

Both the state’s notable “gets”—the improved dismissal rules and the prescription “savings”—could have been accomplished through acts of legislation and should not have been treated as things for which the state must trade.

Governor Lamont in 2019 told the General Assembly he wanted to “show that collective bargaining works.”

But forgoing the legislative process is a needlessly expensive way to achieve policy changes.

The governor and General Assembly, for instance, in 2020 reasserted public access to police discipline records by passing a law that said collective bargaining couldn’t preempt the public’s right to view them.xv Instead of waiting for contracts to expire, and for mayors and first selectmen to make trades at the bargaining table, the General Assembly addressed a matter of serious public concern legislatively.

It is remarkable that any contract or collective bargaining regime could bar a governor from terminating underperforming employees or from offering a voluntary prescription drug savings program.

WHAT THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY SHOULD DO NEXT

The tentative SEBAC agreement would significantly increase costs, and put pressure on both the General Fund and the State Employees Retirement System.

The General Assembly should reject the deal and instruct negotiators to return to the table.

The fact that the state couldn’t offer a voluntary drug savings program without permission from its unions illustrates just how powerful a single special interest has become, and just how heavily the scales are tilted against management.

Instead of ratifying the agreement, the General Assembly should:

- require state negotiators to themselves conduct a uniform cost analysis for any labor agreement, including an actuarial determination about their effect on state pension liabilities; and

- pass legislation to reform the state’s discipline process, offer the drug savings program unilaterally, and bar the state from making any lump-sum payments before Connecticut hits the retirement “cliff” in July.

Endnotes

i. “Connecticut CREATES report,” Boston Consulting Group, 2021. portal.ct.gov/-/media/OPM/Secr-Reports/Connecticut-CREATES-Final-Report.pdf

ii. “Lamont Administration Statement on Tentative Agreement with SEBAC,” 8 Mar 22. portal.ct.gov/Office-of-the-Governor/News/Press-Releases/2022/03-2022/Lamont-Administration-Statement-on-Tentative-Agreement-With-SEBAC

iii. Stuart, Christine, “Lamont Administration To Keep Union Agreement Under Wraps,” CT News Junkie, 25 Mar 22. ctnewsjunkie.com/2022/03/25/lamont-administration-to-keep-union-agreement-under-wraps

iv. Bergman, Julia, “Lamont defends state employee pay hikes,” CT Insider, 5 Apr 22. ctinsider.com/news/article/Lamont-defends-state-employee-pay-hikes-17059901.php

v. For example, Administrative & Residual Bargaining Unit Contract, Article X, Section 3

vi. Fitch, Marc, “Permanent Employees: Only .2 percent of state employees terminated for work performance issues,” Yankee Institute. 15 Mar 21. yankee-institute-dev.10web.me/2021/03/15/permanent-employees-only-2-percent-of-state-employees-terminated-for-work-performance-issues

viii. Lohman, Judith S. “94-R-1095,” Office of Legislative Research, CGA, 23 Dec 94. cga.ct.gov/PS94/rpt/olr/htm/94-R-1095.htm

ix. “SEBAC TENTATIVE AGREEMENT: Breaking it Down, Understanding the History & Preparing for the Next Steps,” SEBAC, 10 Mar 22.

x. “Governor Lamont Submits SEBAC Agreement to the General Assembly,” Governor’s Office, 1 Apr 22. portal.ct.gov/Office-of-the-Governor/News/Press-Releases/2022/04-2022/Governor-Lamont-Submits-SEBAC-Agreement-to-the-General-Assembly

xi. SEBAC Savings Reports, Office of the State Comptroller

xii. Phaneuf, Keith, “How does the state employee health plan compare?” CT Mirror, 4 Apr 16. ctmirror.org/2016/04/04/how-does-the-state-employee-health-plan-compare

xiii. “Fiscal Accountability Report FY22 – FY26,” Office of Fiscal Accountability. 19 Nov 21. cga.ct.gov/ofa/Documents/year/FF/2022FF-20211119_Fiscal%20Accountability%20Report%20FY%2022%20-%20FY%2026.pdf#page=18

xiv. Phaneuf, Keith, “Lamont defends deal with state employees as way to preserve services,” CT Mirror, 5 Apr 22. ctmirror.org/2022/04/05/lamont-says-ct-state-employee-pay-hikes-bonuses-will-preserve-public-services

xv. Public Act No. 21-25

xvi. July Special Session, Public Act No. 20-1