Connecticut’s economic troubles since the 2008 recession are well known. The state has experienced some of the lowest job growth and personal income growth in the country during a time when the national economy surged.

Then, of course, there was COVID and the forced closure of small businesses, restaurants, hotels and entertainment venues across the state.

Between 2008 and 2020, Connecticut borrowed and spent hundreds of millions, if not billions, for forgivable loans, grants and tax credits in an effort to grow jobs, bring in companies from other states or keep companies from leaving, but there was little impact to the state’s economy.

Now, a new study argues there is an easier and cheaper way to jump start Connecticut’s economic engine and lure companies from other states to relocate: eliminate the corporate business tax.

According to Growing from Zero, a new policy paper from Yankee Institute, “Connecticut should pursue transformative policy change that benefits new and existing businesses uniformly – and sends a powerful signal that we’re open for business. There’s no better target than that corporation business tax (CBT), the state’s 7.5 percent assessment on corporate income.”

But eliminating any revenue source in a state that is in perpetual fiscal crisis – not including this year when Connecticut’s budget deficit was solved with federal COVID relief funds – may seem like an impossibility.

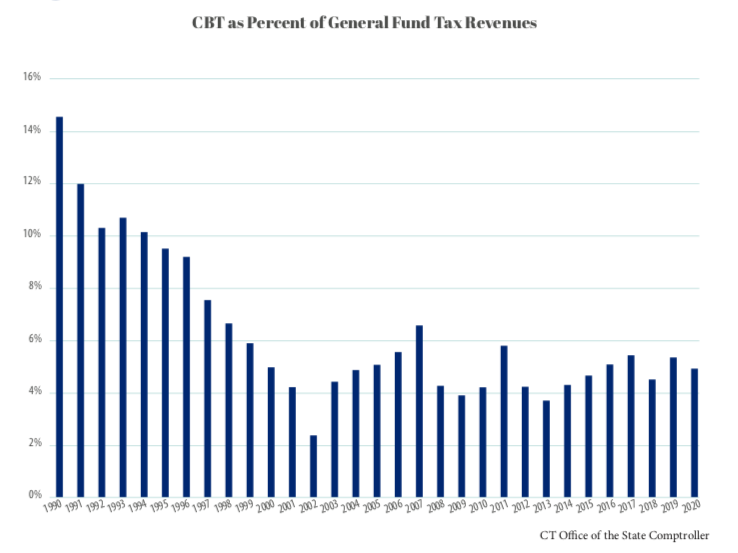

Connecticut’s reliance on the corporate business tax has diminished in the last three decades, going from 15 percent of the budget in 1990 to 5 percent by 2020 and taking in $834 million per year on average over the last five years.

However, authors Ken Girardin, policy director for Yankee Institute, and Daniel Gressel, Ph.D, argue that with New York and New Jersey increasing their corporate taxes, eliminating Connecticut’s corporate business tax could draw in more companies and people, boosting the state’s working population and economy.

They also call for eliminating Connecticut’s practice of offering taxpayer-backed loans, grants and tax credits to businesses for the purpose of increasing or maintaining jobs, the lynchpin of Connecticut’s economic development plan over the last decade.

“State accounting practices don’t give a reliable read of the total cost of economic development programs, but a partial state accounting indicates $1.4 billion in state ‘investments’ under management – which likely would have translated into more private-sector jobs had funds instead been used to reduce or eliminate the CBT,” the report says.

“CBT rate cuts in the late 1990s created jobs at a lower cost per job than many of the state’s existing job-creation subsidy programs,” the report notes.

Gov. Dannel Malloy’s First Five Plus program, a state subsidy program aimed at large corporations, spent $255 million to create a net 3,842 new jobs, according to the study.

The study also highlighted the loss of some major corporate headquarters to other states, like United Technologies and General Electric, but also the diminished presence of some other major corporate entities, noting that Pfizer has only half the number of employees in Connecticut now as it did in 2009.

Connecticut is currently home to 14 Fortune 500 companies, down from 22 in 1990.

However, eliminating the corporate business tax would face a massive up-hill battle in Connecticut where the legislature is largely lead by lawmakers pushing to increase taxes on corporations and once again extended a corporate tax surcharge that brings in between $50 and $80 million per year that was meant to sunset in 2021.

The corporate business tax doesn’t just affect major international conglomerates, but also smaller businesses who are less likely to benefit from Connecticut’s complicated tax credit loopholes and end up paying a higher effective rate than their major counterparts.

Connecticut already awards tax credits and loopholes for specific industries, everything from film and television production to research and development and aviation fuel. Companies can also carry forward business losses to reduce their future tax liability.

As of 2018, Connecticut businesses “had accrued for future use almost $2.9 billion in credits – more than triple what Connecticut collects from the CBT annually,” according to the report.

Essentially, Connecticut corporate businesses are doing what any business, family or individual does – trying to reduce their tax liability – and the complicated mechanisms for doing so may do more harm than good for Connecticut’s economic future.

As it stands now, Connecticut is still over ninety thousand jobs short of where it was in February 2020 and, according to predictions by economists, it could take a while for Connecticut to get back to normal.

But “back to normal” for Connecticut means a stagnant economy and the loss of residents and businesses to other states, while trying to boost the economy with taxpayer money.

“The bulk of Connecticut’s efforts to boost the economy have come in the form of grants, loans, and other direct assistance to preferred businesses,” the report says. “State lawmakers can and should finance CBT repeal by eliminating not only these but also the categorical sales tax breaks, personal income tax credits, and other provisions in the tax code designed to benefit specific industries.”

Kevin Kolenda

July 9, 2021 @ 10:56 am

wow a fwd business thinker in CT . . . I thought I was the only one