The Finance, Revenue and Bonding Committee heard testimony Monday regarding a property tax cap bill that would cap property tax increases at 2.5 percent but allow municipalities to levy a sales or income tax to supplement their revenue.

House Bill 6655 put forward by committee chairman Rep. Sean Scanlon, D-Guilford, would cap property tax increases, offer grant incentives for regionalizing municipal services and let towns and cities levy their own taxes.

The bill received support from the Connecticut Council of Municipalities who have long-supported diversifying municipal revenue streams but was opposed by the Council of Small Towns who argued that there are limited savings opportunities through regionalizing and want relief from unfunded state mandates on towns.

Connecticut municipalities rely on the property tax for roughly 98 percent of their revenue. Connecticut’s property tax – which is also levied on vehicles and business equipment – accounts for Connecticut’s most onerous tax on residents, according to reports from the Tax Foundation and the state’s own Tax Incidence Study.

“We’re over-reliant on an antiquated and regressive tax system,” Scanlon said, labeling Connecticut’s reliance on property taxes as a “systemic problem.”

The 2.5 percent cap is modeled on Massachusetts’ property tax cap that was passed by voters in 1980, however, the Massachusetts law also relieved towns of costly mandates from the state.

Executive Director of COST Betsy Gara said small towns are “very concerned with efforts to move forward with a property tax cap at this time.”

Gara noted that while most towns don’t see a 2.5 percent tax increase in a given year, according to the Advisory Committee on Intergovernmental Relations in 2018 there were 38 towns that increased their budget beyond that threshold.

“It could be because they have a large building project, infrastructure project; it could be because they have an influx of new residents, it could be for a variety of reasons. It could be because they face significant cuts in municipal aid,” Gara said. “Because [property tax increases] are voted on at town meeting or in referendum, it does reflect the will of the residents and their community.”

Concerns over the 2.5 percent limit included collective bargaining agreements, particularly ones related to education budgets, which typically take up at least half of a town’s expenses.

Rep. Tammy Nuccio, R-Tolland, questioned how a town could stay under the cap when teachers are receiving a 3 percent wage increases year-over-year due to collective bargaining contracts while the state is cutting back on some towns’ education funds.

“The loss of revenue under that cap could be problematic,” Nuccio said.

Although the bill would allow municipalities to generate their own sales or income taxes, Gara said many small towns do not have the “commercial base to generate a significant amount of revenue from a local option like that.”

The conversation also revolved around trust in Connecticut’s state government to hold its promises.

Scanlon said the bill would not force any town or city to regionalize, offering a “carrot” in the form of grants that would be provided through the Municipal Shared Revenue Account, rather than penalties or forced regionalization.

However, the MRSA has not been funded by the legislature since its creation in 2015 and Connecticut has a long history of reducing its payments to municipalities for tax-exempt properties and education cost sharing.

Most states, including Massachusetts and New York, have property tax caps in place but how the caps work differ.

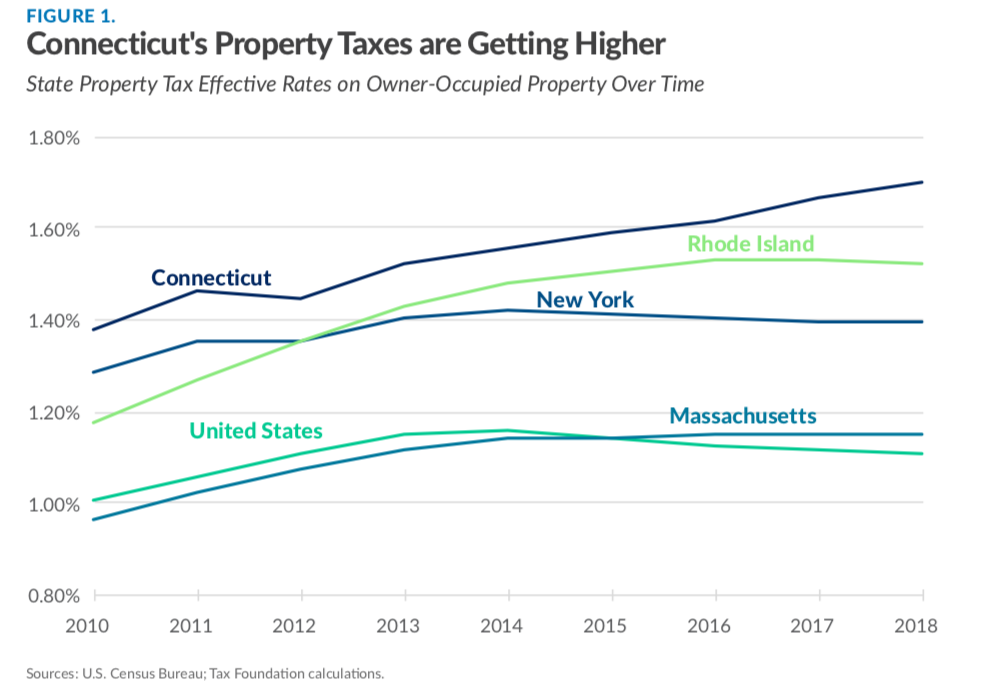

According to a 2020 study released by Yankee Institute and the Tax Foundation, Connecticut’s property tax rate is among the highest in the country and has continued to grow even as property values declined, outpacing all of its neighbors.

New York adopted a property tax cap in 2011, and Gov. Andrew Cuomo claims the cap has saved New York residents upwards of $25 billion. The tax cap excludes five of New York’s major cities.

The language in HB 6655 caused some confusion, however, appearing to limit municipalities to a property tax of 2.5 percent over its net grand list and require towns and cities over that amount to cut 15 percent per year to reach that rate.

Scanlon said the “intent of the bill” is to limit property tax growth to 2.5 percent and says he will work with the clerk’s office to clarify the language.

“This bill is intended to start a conversation,” Scanlon said. “I totally understand that breaking the land of steady habits’ over-reliance on the property tax is not the easiest issue to tackle, but it’s an important one that we have to if we’re ever to address some of the systemic challenges that we face as a state.”

A separate bill to study a potential property tax cap for Connecticut is also being considered.

Bill Generous

April 7, 2021 @ 7:53 pm

the majority of ct towns do have a property tax increase of greater than 2.5%. This article does not consistently differentiate a property tax increase from a property tax rate increase. I’m assuming the proposed bill caps the mill rate increase at 2.5% in non-revaluation years. Most CT town finance officials are not capable of calculating an effective tax rate increase in a revaluation year and often equate the tax increase with the effective tax rate increase in a revaluation year.