Irish immigration to Connecticut can be traced to the early 1600s, hundreds of years prior to the Revolutionary War. While some emigres from the Emerald Isle journeyed across the Atlantic Ocean as adventurers and soldiers, “a far greater percentage came as refugees or enslaved laborers forced from their homes” due to various political upheavals and persecution for their Catholic faith, according to the Connecticut Irish-American Heritage Trail.

Yet the greatest emigration boom after 1789, when the U.S. Constitution was put into effect, came between the 1840s and 1850s when Ireland was devastated by the Potato Famine. Prior to 1845 when the blight began, more than 8 million populated Ireland; however, hundreds of thousands died of starvation and disease because of the massive crop failures, while 1.8 million fled the country, greatly reducing the island’s population by more than 2 million by 1851 (or 20 percent).

As noted by the Connecticut Irish-American Heritage Trail, many of the emigres sailed for the United States, and Connecticut’s “Irish-born population jumped from less than 5,000 in 1845, to 26,689 in 1850, and 55,445 by 1860.”

When the Irish arrived, they faced discrimination (i.e., ‘No Irish Need Apply’), and most could only find work as unskilled laborers who provided the “backbreaking and low-cost manpower needed to construct new infrastructure projects such as canals, roads, railroads, bridges, and dams,” as stated by the Connecticut Irish-American Heritage Trail.

Despite contemporary nativist fears concerning the influx of poor, illiterate and Catholic immigrants, the Irish were resilient, firmly establishing themselves as citizens in their adopted country.

They were brave and patriotic, as well. According to the Connecticut Irish-American Heritage Trail, at the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, “Irish-born or first-generation citizens volunteered for service in efforts to preserve the Union at an incredible rate,” totaling approximately 8,000 out of the 54,000 enlisted men from Connecticut.

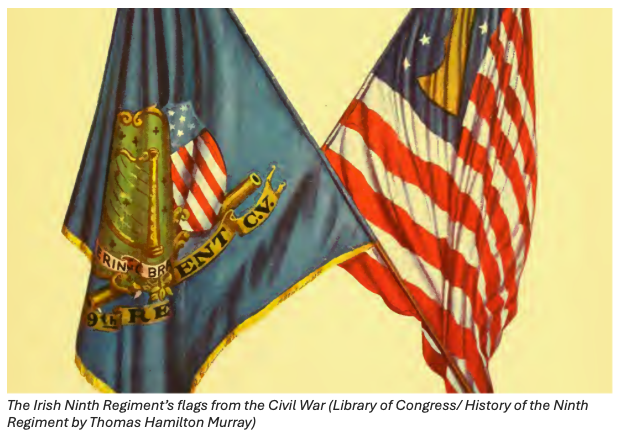

While an Irishman could be found in any New England regiment, 1,200 fought in Connecticut’s Ninth Regiment Volunteer Infantry. From Virginia to Louisiana, the Connecticut Irishmen engaged in more than 10 battles under a “blue banner emblazoned with a golden harp on a field of emerald, green dotted with shamrocks and bearing the motto ‘Erin Go Bragh,’” meaning ‘Ireland Forever’ in Gaelic, according to Connecticut History.

This is the story of the Ninth Regiment — also known as the ‘Irish Regiment.’

‘An Intense American Spirit’

Anti-Irish prejudice nearly prevented Eire’s sons from enlisting in military service. In 1855, Gov. William Minor, who was elected as a member of the nativist “Know-Nothing” Party, dissolved “six state militia units made up of Irish immigrants, even though most were naturalized U.S. citizens” for being “detrimental to the military interests” of the state, according to Connecticut History.

As governor, Minor also “restricted voting rights, wrestled control of Catholic Church property from its hierarchy and called for waits of up to 21 years for citizenship,” as noted by The Hartford Courant. Yet he occupied the office for only two years, as gubernatorial elections were held yearly at the time. By April 1861, William Buckingham — Connecticut’s first Republican governor — held the office and “authorized [the] formation of the Ninth Regiment as a specifically Irish unit,” after the Battle of Fort Sumter, which sparked the war.

Men from 79 municipalities across the state, including 400 from New Haven and a 12-year-old drummer boy named Richard Hennessey, readily joined the newly formed regiment, organizing in the summer of 1861 in Hartford, then forming at Camp Welch in the Elm City under the command of Col. Thomas Cahil in September. In History of the Ninth Regiment by Thomas Hamilton Murray, published in 1903, the author describes the Irishmen’s zeal to serve, writing, “In no regiment that went to the front was there a more intense American spirit or more loyal devotion to the cause of the Union.”

However, their zeal was not mitigated by the disadvantage of “not having arms,” according to Murray; the Ninth Regiment’s men were “devoted to marching and other evolutions” and “rapidly learned the duties of the soldier, in camp and on the march, and were also instructed as to manoeuvres [sic] in skirmish and battle.”

From Murray’s historiography, “general good humor prevailed” at the camp, despite the lack of guns to drill with. As a predominantly Catholic regiment, faith was vital to the men, who attended Mass at St. John’s Church every Sunday, except on one occasion when Mass was celebrated at Camp Welch. The regiment also had a chaplain (Rev. Daniel Mullen) from Nov. 17, 1861, to August 1862, although he resigned due to poor health.

After several months of training, the Ninth Regiment received orders to join a New England Division led by Major-Gen. Benjamin Butler at the behest of Gov. Buckingham. A few days before the troops departed, the regiment was presented its colors: a flag of the Union and the State with the inscription ‘Erin Go Bragh,’ the latter which was a “gift of a number of patriotic ladies.” According to The New Haven Palladium, the presentation moved several of the officers, including Major Frederick Frye:

“He regarded the gift as a sacred trust, which would, under all circumstances, be sacredly defended. He trusted that on the return of the regiment these colors would be brought back with it, and if soiled, it would only be by the dust and smoke of battle, but in other respects they would be more glorious than now, new and gorgeous as they have been made by the fair hands which presented them.”

On Nov. 4, 1861, the Ninth Regiment left New Haven for Camp Chase in Lowell, Mass., for a brief stay, embarking on a steamer — the Constitution — from Boston to Ship Island, Miss., later in the month. By Dec. 3, the Connecticut troops were in Confederate territory. According to the Connecticut National Guard’s history, the island was “abandoned by Confederate forces following an engagement with the U.S. Navy and since then became an offshore hub of logistics and quarters” for the Union Army. While the regiment still retained the “buoyancy of Irish character” at Ship Island, even “appropriately celebrat[ing]” St. Patrick’s Day, the conditions were harsh from December until April. As Murray recounts:

“The men were still wretchedly clad, and it was midwinter. Nearly half of them were without shoes and as many more without shirts; several had no coats or blankets. Some drilled in primitive attire of blouse and cotton drawers. The tents were hardly capacious enough to cover them. There was no straw to sleep on. They were without transportation, and were obliged to bring the wood for their fires four miles.”

After months at Ship Island, the Ninth Regiment finally received orders on March 29 to head toward New Orleans, La. Yet it was soon learned that 1,800 Confederates were at Pass Christian, Miss. It was there, on April 4, the Ninth Regiment had its first taste of battle, defeating the Third Mississippi Infantry. With news of the victory, Gov. Buckingham wrote to Col. Cahill, “It is hardly necessary for me to say that the conduct of your men meets my cordial approval, and I am proud of both officers and their command.” Respect for the Irish had come a long way since the mid-1850s.

In the ensuing weeks, the Ninth Regiment participated in “some smaller actions, such as the operations against Fort St. Philip and Jackson and would eventually be moved to New Orleans” by the end of April 1862, according to the Connecticut National Guard. The Union’s occupation of the Big Easy had serious difficulties due to some saboteurs; one harrowing incident was the murder of Mark O’Neill from the Ninth Regiment on May 4, 1862. To squash residents’ “ugly mood” against the federal soldiers, Gen. Butler selected the Irish Regiment to parade through the city, which was “an honor the regiment duly appreciated.”

After nearly two weeks in New Orleans, the Ninth Regiment moved to Baton Rouge. This stay was also brief, as they headed to Vicksburg, Miss., in June. It was there the Ninth Regiment truly encountered the horrors of war — and its largest casualties.

The Other Fighting Irish

The Connecticut National Guard succinctly suggests that Vicksburg “became hell on Earth for the soldiers of the Ninth.” The city was a critical strategic point for both the Confederacy and the Union armies because whoever controlled Vicksburg would effectively control the Mississippi River. However, the Union did not have the manpower for a direct assault.

To bypass a confrontation with the Confederate stronghold and “open a passageway for U.S. Navy gunboats,” Brigadier-General Thomas Williams tried to construct a massive canal from De Soto Point in Louisiana to the city. The Ninth Regiment were enlisted to assist in the engineering feat, reporting for duty on June 25, 1862.

Soon after, men began succumbing to not only disease, but the southern heat. On the latter, Capt. Lawrence O’Brien recalled Gen. Williams’ seemingly little concern for his soldiers’ well-being:

“Gen. Williams was not in sympathy with his men. He exacted the most rigid discipline. Notwithstanding the great amount of sickness prevailing, he ordered the brigade to parade every day, in marching order, with knapsacks packed. I saw men drop out of the line exhausted, and when we returned many of them would be dead. This drill and parading was done when the thermometer registered 110 to 115 in the shade.”

By late July, more than 150 men in the Ninth Regiment died. Due to fatigue and the loss of life, work on the ill-fated canal ceased. It would never be completed even after Gen. Ulysses S. Grant took command of the Vicksburg campaign in 1863. After months of a siege, the Union eventually won a decisive victory in December that year.. After months of a siege, the Union eventually won a decisive victory in December that year.

The Ninth Regiment was not in Vicksburg after July 1863. They were ordered back to Baton Rouge to hold a defensive position. However, the reprieve only lasted until August 5, 1863, when Confederate forces led by Maj.-Gen. John Breckenridge — who had once been vice president of the United States during the James Buchanan administration — tried to recapture the city. During the battle, John C. Curtis of Bridgeport displayed exemplary valor when he “voluntarily sought the line of battle and alone and unaided captured two prisoners, driving them before him to regimental headquarters at the point of the bayonet,” according to his Medal of Honor citation. He would be the only member of the Ninth Regiment to receive the distinction. . He would be the only member of the Ninth Regiment to receive the distinction.

One member of the Ninth Regiment was killed, nine wounded, and four were missing in action. According to the Connecticut National Guard, the Irish regiment returned to New Orleans to defend the city until April 1864. As the site states, “During this time, the regiment simultaneously sent out detachments for expeditions such as the expedition to Ponchatoula between March 21 and March 30, 1863.” The regiment detachments also engaged in combat including at La Fourche Crossing (June 1863), Chattahoola Station (June 1863) and Pass Manchac (March 1864).

On April 15, 1864, after more than two years away from home, the Ninth Regiment returned to Connecticut for a veteran furlough and was greeted by great fanfare from New Haven’s residents. They were escorted to New Haven’s State House, where Mayor Morris Tyler addressed them, as well as Father Hart, who said:

“You have done well. We are proud of you. Other regiments have fought more than you because they had it to do. You have done all the fighting given you to do, and done it well. We honor you, therefore, and were proud of you when we heard of your congratulatory orders, and your compliments for discipline and bravery.”

The men had a chance to visit their homes and families. But the temporary peace came to an end on July 18, 1864, when the Ninth Regiment set out again — this time to Virginia. Their first action was in Deep Bottom, Va., from July 28-29; however, the Ninth Regiment’s next major engagement was the Battle of Winchester (Sept. 19, 1864), which “would become the first defeat for a Confederate general in the Shenandoah Valley and one of the most costly battles of the war,” according to the Connecticut National Guard. Two Confederate generals were among the 4,000 casualties, and more than 1,700 became prisoners of war. During the battle, the Ninth Regiment was “thrown forward as skirmishes and to protect the right flank of the Nineteenth corps,” and “the videttes of the regiment were the means of having a Confederate battery captured, as they kept fighting firing at the gunners and thus greatly aided a regiment of the Eighth corps which came up and took the battery,” as noted by Murray..

The Ninth Regiment fought in two other battles at Fisher’s Hill and Cedar Creek, both in the fall of 1864. On Oct. 12, 1864, the regiment was re-organized as a battalion becoming the Ninth Battalion, according to the Connecticut National Guard. The Connecticut Irishmen spent the rest of the war on duty in the Shenandoah Valley and then in Savannah, Ga.

Throughout the Civil War, 253 of Connecticut’s Ninth Regiment lost their lives, making the ultimate sacrifice. On Aug. 3, 1865, the Connecticut troops returned home with their colors, this time for good.

Parting Glass

In January 1879, the General Assembly passed a resolution to move Connecticut’s battle flags, including the Ninth Regiment’s colors, from the State Arsenal to the new Capitol building’s Hall of Flags.

The flag is still there today, encased behind glass for preservation. And around the 20th century, the City of New Haven erected a monument in honor of Connecticut’s Irish soldiers in Bay View Park on Aug. 5, 1903.

For a people who had been heavily discriminated against in their newly adopted country, Connecticut’s Irishmen never succumbed to the temptation to see themselves as victims— rather, they readily enlisted to fight and spill their blood to repair a nation. Perhaps they were fueled by their famous Irish stubbornness; more likely, they recognized in America a country where they could — at least one day — build new, better lives than the ones they suffered under throughout British rule in the 19th century.

As once stated in this newsletter, America’s history is not sinless, as evidenced by the anti-Irish prejudice. But its ideals and principles are worth striving toward. The Irish people’s perseverance, sacrifice and now widespread acceptance (where everyone is proudly “Irish” on St. Patrick’s Day) reflects how those ideals — that all men are created equal and that they can pursue happiness here — have been and always will be alive if a people keep them.

So, this St. Patrick’s Day, I’ll be filling a parting glass for those veterans in the Ninth Regiment and my Irish forefathers (from County Kerry and Sligo), who helped build this great country and pray ‘Erin Go Bragh’: Ireland forever.

Till next time —

Your Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Andy Fowler