Near the Antarctic Peninsula, on Anvers Island, are two buildings and several smaller structures that provide year-round housing and research facilities for 20 people, including scientists and other support staff. Originally constructed in 1965, the compound is the only U.S. station north of the Antarctic Circle (at 64° 46°S, 64° 03°W).

Life is not as brutally harsh as one might expect at the bottom of the Earth. According to the U.S. Antarctic Program, average temperatures are 36 degrees Fahrenheit in summer and 14 degrees in winter; high wind speeds intensify the chilly conditions, however, and the annual precipitation is 13 feet of snow and 30 inches of rain. Like the northern Arctic, the landscape basks in the sun’s illumination for 19 hours a day in the summer — but has only five hours of light in the dark winters.

This station is named in honor of the man who, while on a sealing expedition in November 1820, became the first American to record sighting the Antarctic continent: Nathaniel B. Palmer of Stonington, Conn.

His matter-of-fact log on the vessel Hero and biography — Captain Nathaniel Brown Palmer: An Old-Time Sailor of the Sea by journalist John R. Spears — reveals a man intent on mission for economic prosperity, rather than the exploratory ambitions akin to Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, Amerigo Vespucci or James Cook. Still, a mountainous stretch of the continent’s southern peninsula that his sloop sailed along also bears his name, Palmer Land and the Palmer Archipelago.

This is the story of Palmer’s historic trip to the end of the world.

An Experienced Sealer

By the early 1800s, the New England whaling and sealing industries were vital to the state’s economy — providing leather, as well as oil for soap, margarine and lamps. But they were also exploitative. Overhunting resulted in “large fluctuations in harvest and shift in hunting grounds” to the point where “seals were almost exterminated in some locations,” according to The 19th Century Antarctic Sealing Industry. However, these industries would eventually collapse due to the “burgeoning petroleum and gas industry” lessening the “need for oil made from blubber” at the turn of the century, along with the rise of animal rights activism.

Regardless, Stonington was instrumental when both industries thrived — and town native Nathaniel Palmer was drawn to the sea at an early age. His father, Walter, worked in shipbuilding, so the boy “had a shipyard for a playground from the time he was old enough to run around without the care of a nurse,” and “absorb[ed] a knowledge of hulls and spars before he went to school to learn his letters,” according to his biography.

Yet by Palmer’s early teens, tensions between the United States and Britain reached a breaking point when the latter continued blockading American shipments to France (with whom Britain was at war ), along with impressing more than 10,000 U.S. sailors into the British navy. The United States declared war on Britain; thus the War of 1812 commenced, and Stonington became a target for blockades, and even a battleground in August 1814. The young 14-year-old Palmer joined blockade-runners and “trained to handle the tiller” — the lever to steer the ship — at which he quickly became an expert. As Spears notes:

“In fair winds and foul; in gentle airs and in roaring gales, he had to stand his trick at the tiller, noting the while not only the influence of the wind but the influence of tidal currents, which were sometimes favorable and sometimes adverse. More important still, considering the work he was to do later, he had to do all this at night and when the fog was so thick on the water that he could not see the jib [a triangular sail] when he stood at the tiller.”

The war ended in 1815 after the Treaty of Ghent’s ratification; but Palmer was hooked on the sea, sailing on trade ships between New York and New England ports until 1818. With his proven ability, he became master of the schooner Galena before he turned 19. Soon after, Palmer was “invited” to be second mate on the Hersilia’s 1819 expedition to “explore unknown waters below Cape Horn” and find new sealing hunting grounds that had been pushed further south.

At this point, Palmer had no experience in sailing outside the New England and New York corridor — yet he joined the crew that left Stonington in July. Over the next several months, his “wit and knowledge” would prove invaluable. While gathering supplies on the Falkland Islands, Palmer interacted with British sealers and deduced their course to the present-day South Shetlands — a group of islands nearly 75 miles north of the Antarctic Peninsula. Finding new rookeries (or large assemblies of seals) there, the Hersilia’s mission was a financial success.

The crew sailed home, and Palmer was poised to be a “captain of a most important vessel” in the next expedition southward.

‘An Unexplored Island of Large Size’

The excitement was palpable with the Hersilia’s return to Stonington. According to Spears, “owners of suitable vessels at Salem, Boston, Nantucket, New Haven and New York began to fit out expeditions to compete with Stonington” for the newly discovered rookeries.

Five brigs and two schooners were added to the upcoming expedition’s fleet commanded by Capt. Benjamin Pendleton, and a new 47-foot sloop — a sailboat with one mast — was constructed: the Hero. This was the vessel Palmer captained in 1820. But the challenges would be immense, as Spears describes:

“Because of the character of the work the Hero was to do and because of the vile weather in which it was to be done, a master was needed who was at once venturesome, courageous, and withall [sic] able to handle a sloop rig; and young Nat Palmer was the chosen to fill it.”

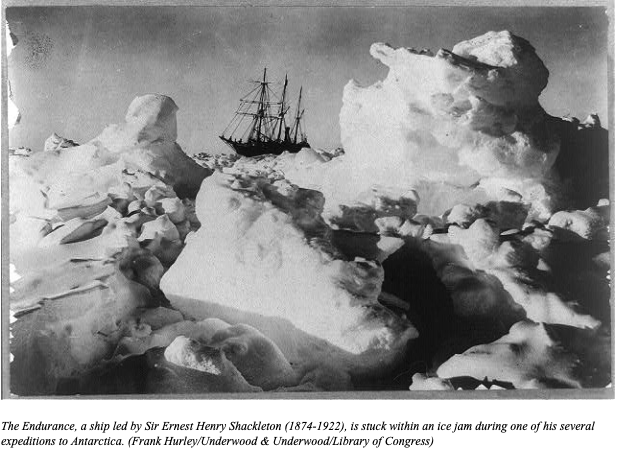

When the fleet arrived in the South Shetlands, the rookeries had already been “depleted rapidly” and the “decrease naturally led all the captains of the vessels” to discuss a search for another. The group concluded that Palmer should lead the exploration — so the Hero went off, more than 200 miles from Yankee Harbor where the rest of the fleet waited. The mission was no easy task: Palmer and the Hero’s five-member crew were sailing in a region “which had never been visited by man,” as Spears claims, traversing “among floating fields of ice and uncharted reefs” in “hurricane squalls with blinding snows.” If the Hero encountered any troubles, it would have been a death sentence as there was “no hope of a rescuing party ever finding the wreck.”

Nevertheless, Palmer’s crew carried on, with Spears suggesting they were even “thrilled.” However, the timeline from when the Hero set sail to find new islands and rookeries versus the eventual discovery of Antartica varies. Spears places Jan. 14, 1821, as the date Palmer “was to place him beside Columbus,” citing the log entries from Capt. Pendleton. However, Palmer’s own logs from November 16 and 17, offer a different story.

The former’s entry describes, quite possibly, the first recorded sighting of the continent, though it is lackluster in details beyond “fresh Breeses [sic] from SW and Pleasant”; the latter’s is more descriptive:

At 4 A.M. made sail in shore and Discovered-a-strait- Tending SSW&NNE it was Literally filled with Ice and the shore inaccessible thought it not Prudent to Venture in we Bore away to the Northw’d and saw 2 small Islands and the shore every where [sic] Perpendicular we stood across toward Freseland [Livingston Island] course NNW the Latitude [sic] of the mouth of the straight was 63.45 S End with fine weather SSW.

In 1834, Palmer recounted the seminal event to a colleague with more emotion, saying the ship “seemed to enter into the spirit which possessed my ambitions, and flew along until she brought me into the sight of land not laid down on my chart.” According to Spears, the crew first saw two mountains, the highest peak later being named Mount Hope (though not by any member of the Hero — but by American naval officer Charles Wilkes during an 1840 expedition). To the Hero, Antarctica was a “rugged, verdureless land” and a “most desolate region”; however, “when the sun was shining, with the green waters along shore dotted with gleaming ice cakes, and with the air filled with thousands of gray and black petrels and white cape pigeons, it was strikingly beautiful.”

Despite the striking beauty, Palmer believed then the land to be “simply an unexplored island of large size, or perhaps a group of islands” because, as Spears comments, “little attention was given to any new coast unless it afforded a prospect for profitable exploration.”

Yet, while the Hero sailed along Antarctica’s coast, the crew encountered two Russian warships on an exploratory expedition. There were no hostilities, but instead, a fraternal atmosphere among the American and Russian sailors. In a conversation between the two captains, the 22-year-old Palmer told the Russians of land further south and shared his logs, much to the pleasure of his hosts; in this exchange, the Russian captain reportedly named the discovered land after the Hero’s captain. Today, the area is known as Palmer Land.

Second Star to the Right, and Straight On Till Morning

Without pomp or circumstance notwithstanding the momentous discovery, the Hero sailed for home on Feb. 22, 1821, with a “fine breeze from (the) west,” according to the sloop’s log. Overall, the fleet’s expedition was financially successful “due to the fact that populous rookeries were found by Captain Palmer in his first cruise among the islands.”

In subsequent years, Palmer turned his attention from sealing to international trade, transporting troops and supplies to Simón Bolívar — a Venezuelan revolutionary who led an independence movement against the Spanish — as well as shipbuilding, including developing clipper ships. He died on June 21, 1877, at 77 years old. Meanwhile, his home has been preserved as the Captain Nathaniel B. Palmer House Museum in Stonington.

But did Palmer — at 22 years old — truly discover Antarctica? There are conflicting claims that Russian or British sailors first set eyes on the southernmost continent in early 1820. By the 1950s, seven countries — Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and the United Kingdom — claimed territorial sovereignty over areas they discovered, according to the Library of Congress’ “History of the Antarctic Treaty System.”

To avoid further geopolitical tensions during the Cold War, 12 countries — including the United States and Soviet Union — met and “agreed that their political and legal differences would not interfere with the shared goal of scientific discovery and research on the continent” at the International Geophysical Year of 1957-1958. The result was the Antarctic Treaty, which was signed in the United States by the 12 participating countries on Dec. 1, 1959. As part of the pact, “no country can claim territorial sovereignty over any part of the continent.”

Whether or not Palmer was the first to see Antarctica is still uncertain; more than likely, he was not. It’s undisputed, however, that the Connecticut native was the first from America.

What’s also undisputed is Palmer’s courage at such a young age. To navigate through the treacherous ice on a small 19th century sloop with five crew members is an achievement of the human spirit — whether it was inspired by curiosity or simply by the desire for economic prosperity (aren’t most advancements in scientific and human achievements inspired by the latter?).

Though the age of discovering new lands has shifted from the seas to the stars, perhaps Connecticut residents may find inspiration in Palmer’s expeditions, and pursue new innovations that enlighten and expand our finite worldview of the universe’s grandness. May we chart a new course toward freedom and prosperity for the betterment of all.

Till next time —

Your Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Andy Fowler