There was “little interest” from the Massachusetts Bay Colony to expand into the Connecticut Valley when a delegation of sachems offered land in exchange for protection against the Mohawks and Pequots.

Yet the English reconsidered the proposition after the Dutch established a trading post — the House of Good Hope — on the Connecticut River near present-day Hartford, a “major transportation artery” with “access to promising fur trade,” according to the Windsor Historical Society. In September 1633, a party from Plymouth, led by William Holmes, sailed up the Connecticut River and settled by the Farmington River despite threats of cannon fire from the Dutch.

The village eventually became Windsor: the first English settlement in Connecticut.

However, the Windsor settlers encountered much turmoil in the early years, particularly tensions with the Pequots that erupted in a “quick and brutal engagement,” leading to the “decimation” of the tribe in 1638.

This is the turbulent world Alice Young encountered upon arriving from London in 1640. Not much is known about her — there are only hints by historians who have conjectured about why she may have become a “pariah” in the village. She may have had a husband named John and at least one child. However, after influenza ravaged Windsor in 1647, residents levied a catastrophic charge against Young: that she was a witch.

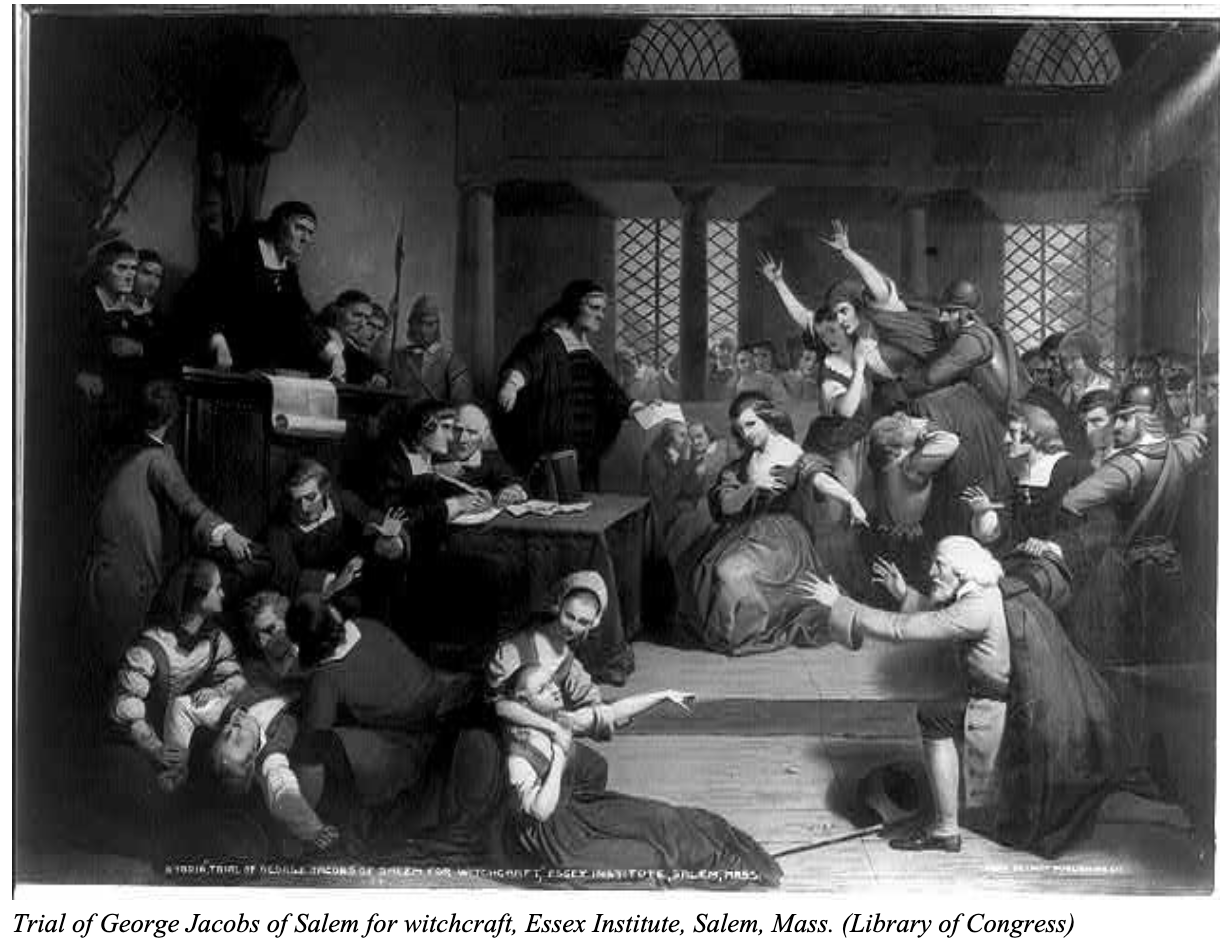

Why Windsor settlers accused Young in particular remains unclear. But only several years earlier, in 1642, Connecticut’s colonial government had decreed witchcraft to be a capital offense. Unfortunately for Young, she was convicted after a trial. On May 26, 1647, she became the first person in the colonies to be executed for witchcraft. Her hanging was at Meeting House Square in Hartford.

But Young would not be the last. In truth, Connecticut endured one of the worst “witchcraft panics” in colonial America, nearly 30 years before the more famous trials in Salem, Massachusetts. Ultimately, nine women and two men were executed between 1647-1663, with plenty more accused until the beginning of the 18th century.

This is an exploration of the first witchcraft trials in America, and the eventual exoneration of the dead more than 370 years later.

‘I Have Given You My Soul, But Leave Me My Name’

Witchcraft panics had been common in England by the early 17th century. When King James I (or VI of Scotland) assumed the throne after Queen Elizabeth I’s death, he had a particular interest in the Copenhagen witch trials, and became “convinced a witch had cursed his fleet, causing them to face a terrifying storm while returning to Scotland from Denmark,” according to Oxford Castle & Prison.

The king and Parliament enacted the Witchcraft Act of 1604, reforming previous laws that transferred the trial of ‘witches’ from the Church to the ordinary courts. In reaction, a resurgent fear gripped the country. The accused were often poor, older women; and proof could have been “a third nipple, an unusual scar or birthmark, a boil, a growth, or even owning a cat or other pet,” according to the British Library. However, claims of witchcraft reached a peak during the English Civil War (1642-1651) led by Puritan Oliver Cromwell.

Between the 15th and 17th centuries, historians estimate nearly 500 were executed as witches.

When the Puritans emigrated to the Americas, their legal code was predicated on Old Testament biblical passages such as Exodus 22:18 (“Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live”) and Leviticus 20:27 (“A man also or woman that hath a familiar spirit, or that is a wizard, shall surely be put to death”), as explained by Christopher Klein in “Before Salem, the First American Witch Hunt” for History.com.

Thus, paranoia also emigrated to the New World. With epidemics, economic hardships and the influence of non-Christian Native American ceremonies, New England was “ripe” for witch hunts.

Only a year after Alice Young was hanged, Mary Johnson of Wethersfield was executed after “allegedly confessing to entering into a compact with the devil,” according to ConnecticutHistory.org. The next victims of the hysteria were John Carrington — a carpenter — and his wife, Joan, also of Wethersfield. Though the documentation for their trial (like many others of the period) are mostly lost to time, John’s indictment has survived, which accused him of:

“not having the fear of God before thine eyes thou has Entertained familiarity with Satan, the great Enemy of God and mankind and by his help hast done works above the Course of nature for which both according to the Lawe [sic] of God and of the Established Lawe [sic] of the Commonwealth, thou deservest to die.”

What raised the suspicions of John and Joan Carrington’s neighbors is also unknown. They were executed in 1651, as was Goodwife Basset of Stratford. Again, little is known about Basset or the trial, though Gov. John Haynes presided over the case and she reportedly confessed to her crime — likely after being tortured.

In 1653, Fairfield residents suspected Goodwife Knapp to be a witch. She underwent a multi-day trial overseen by Roger Ludlow — a founder of Connecticut — and was accused of having unique (or sinister) marks on her. Knapp was hanged in the Black Rock section of town (around 2470 Fairfield Avenue), and after her body was cut down, reportedly “the women of the town crowded around to see the ‘witch marks’ but found nothing.”

One of the stranger trials occurred nearly two years after the case’s inciting incident. Henry Stiles, a single man, was boarding with Thomas and Lydia Gilbert of Windsor. On Nov. 3, 1651, Stiles was killed by a neighbor, Thomas Allyn, when the latter’s gun discharged during training exercises with the local militia. Allyn confessed to “homicide by misadventure,” and then fined by the court. After paying 20 pounds, he was released into his father’s custody. Yet residents believed something more sinister was afoot with the gun’s discharge — and after several years their ire eventually turned on Lydia Gilbert. She was indicted, tried and found guilty in November 1654; though “Legends of America” concludes that her ultimate fate is unknown, they state “most historians believe that she was hanged” in Hartford.

Nearly ten years passed and then the healthy, eight-year-old Elizabeth Kelly mysteriously died in 1662. Her death ignited the worst witchcraft hysteria in the colony. Shortly after Kelly’s death, the “pious” Ann Cole became bewitched, “shaking violently and spouting blasphemy,” according to History.com. During one fit, she claimed evil spirits were “conspiring how to carry on their mischievous designs against her” as two ministers were attempting to help her. Cole blamed her condition on neighbor Rebecca Greensmith, who was imprisoned on the suspicion of witchcraft. According to “Legends of America,” she also was not well regarded by Rev. John Whiting, who described her as “lewd, ignorant and considerably aged.”

In interviews with authorities, Rebecca confessed to a “familiarity with the devil” and meeting with him to form a covenant at Christmas — but claimed that she wasn’t alone: others involved were her husband Nathaniel, Andrew and Mary Sanford, Elizabeth Seager, and William and Goody Ayres. All of them were allegedly dancing in the woods — which was a sign of lewdness in Puritanism. Although Nathaniel maintained his innocence in court, Rebecca did not, and both were executed along with Barnes. Mary Sanford also did not escape the gallows, though the grand jury “couldn’t agree on the indictment against” her husband, Andrew. He was acquitted — and so were the Ayres, who fled Hartford after the trial. Seager, meanwhile, was initially acquitted, but then indicted again in 1665 for witchcraft. This time she was convicted, but, as fate would have it, Gov. John Winthrop reversed the verdict.

While another panic “broke out” in Fairfield in 1692, none of the accused were put to death. According to History.com, Connecticut’s final witch trial was held in 1697, with the Benhams of Wallingford escaping a trip to the gallows.

It would take more than a half century until the crime of witchcraft disappeared from the list of capital crimes. The hysteria that had cost the reputation and lives of so many officially ended.

The Road to Exoneration

Although centuries have passed, the panic’s scars remained for the descendants of those accused, convicted and executed. Yet the road to exoneration, a movement that solidified in the 2000s, had a few bumps, including a 2008 resolution that failed to get out of committee, and an unsuccessful request by then-Gov. Dannel Malloy for a proclamation in 2012. Advocacy groups such as the Connecticut Witch Trial Exoneration Project have led the way in the effort to educate and establish a “permanent memorial to the victims of the witch trials.”

Towns like Windsor exonerated Alice Young and Lydia Gilbert on Feb. 6, 2017, 370 years after the former’s execution. But the state had made no official statement until the passage of House Joint Resolution 34 that “absolved of all crimes of witchcraft and familiarities with the devil.”

“It doesn’t matter how many generations back she is,” said Kimberly Black, a descendant of Mary Sanford, to the Judiciary Committee earlier this year. “Without her existence and without her struggle, I would not be here today.”

Likewise, Suzanne Vogel-Scibilia — a descendant of John and Joan Carrington — testified that “This may seem like an old issue, irrelevant now after being buried over the centuries, but I have difficulty telling my young granddaughters, Josehine, Liesel and Mathilde, about what happened to their ancestors.”

As Sen. Saud Anwar (D-3rd), one of H.J 34’s co-sponsors, put it to the CT Mirror: “People are experiencing generational trauma, and they want closure.”

The resolution also stated that “misogyny played a large part in the trials and in denying defendants their rights and dignity.” Those who publicly testified in H.J. 34’s favor, like Black, cited misogyny and deviation from Puritan social norms as the basis for the executions. Black told the Judiciary Committee that the trials were about “destroying the Feminine so patriarchy could rule.” Meanwhile, Jess Zaccagnino — policy counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Connecticut — added that the “informal legal proceedings that decided these people’s fates do not meet today’s modern standards of proof, and were much more influenced by fear and moral panic rather than actual law.”

Josiah Schlee was one of two objections to the resolution during public testimony, arguing for the exoneration of “people who are in prison now” for cannabis possession.

The General Assembly sided with the exoneration movement, overwhelmingly passing the resolution with the House tally at 121-30, and the Senate at 33-1.

As the state officially closed the chapter and the advocacy now evolves into the memorialization phase, Windsor has already taken that step, setting two red bricks in the town green’s north end with Young and Gilbert’s names inscribed on them. It may have taken centuries, but as the aphorism goes, time does, indeed, heal all wounds.

May the victims rest in peace.

Till next time —

Your Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Andy Fowler