Since the November elections, Gov. Ned Lamont and lawmakers have proposed revisiting the way Connecticut residents vote, offering ranked choice voting as an alternative. Several pieces of legislation have been introduced, including House Bill 5712 that would establish a task force to study the option in certain elections.

Municipalities across the country utilize it, most prominently in Maine and Alaska for all state and federal primary elections and all general congressional elections; and state and federal general elections, respectively.[1]

But what is ranked choice voting and how does it work?

With the concept gaining momentum, Yankee Institute decided to uncover what ranked choice voting would mean if implemented in Connecticut. On the surface, ranked choice voting sounds like an attractive, more ‘democratic’ electoral process; however, it can pose more problems and lead to less democratic outcomes.

What is Ranked Choice Voting?

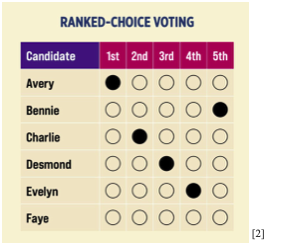

In contrast to plurality elections, in which the candidate with the most votes wins, ranked choice provides voters the option to rank-order candidates on their ballots. For example, voters may have the ability to rank five or six candidates on the ballot in their order of preference:

If a candidate wins more than 50 percent of first-place votes, they are declared the winner. If no candidate gets a majority of first-place votes, then that will prompt a new counting process. The candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated; so, if a voter ranked the losing candidate as their first choice, and that candidate is eliminated, then their second option replaces the first. This process will continue until a candidate receives a majority of votes. In a perfect world, this may take one or two rounds of tabulation. However, races with larger fields can require multiple rounds of tabulations,[3] which often causes ‘ballot exhaustion,’ along with other issues including information deficits, confusion and disenfranchisement.

Exhausted Ballots can prevent certain voters from having their votes counted

Ballot exhaustion occurs when a ballot is untallied because none of the marked candidates remains in the contest.[4] Since these votes are not tabulated in the final round, a voter’s ballot would not count — as if they, effectively, never went to the polls on election day. That voter is effectively disenfranchised.

Other examples of exhausted ballots include overvoting and undervoting. The former occurs when a voter marks two candidates in a single column, which eliminates the ballot from the count. The latter occurs when a voter skips two or more columns in the preliminary round. For example, if a voter does not select a second or third choice, instead voting only for their first and fourth choices, their ballot would not be counted.[5]

Information deficits are amplified under the ranked choice voting system

Plurality elections are relatively straightforward: pick your single favorite candidate of those on offer. However, the reality is that many American voters have scant knowledge about candidates’ stances on important issues. A ranked choice system exacerbates this issue, placing voters in a position where they need to be informed about multiple candidates.

To illustrate, a Pew Research Center survey conducted prior to the 2016 Presidential Election revealed that a significant proportion of registered voters knew little or nothing about where the two major party candidates stood on key issues.[6] When a voter is confronted with ranking candidates, he or she may do so completely arbitrarily. This is already an issue in plurality elections; it will only be amplified in ranked choice elections — and will overwhelmingly favor incumbents, who have the advantage of greater name identification.

Less knowledgeable voters are liable to rank fewer candidates, while more knowledgeable voters are likely to rank more candidates. When presented with a ranked choice ballot, many voters do not rank every candidate, potentially due to inadequate information about them. This can lessen the influence of less knowledgeable voters, resulting in a less democratic voting process.

Ranked Choice can lead to confusion and disenfranchisement

After Maine implemented ranked choice, voter confusion was so prevalent that supporters of the system felt compelled to publish a 19-page instruction manual to help voters understand the process.[7] Because the process of filling a ranked-choice voting ballot is challenging, error rates for ranked-choice voting elections remain higher than those of traditional elections.[8] As a result, many voters are having their ballots thrown out because they couldn’t adhere to the convoluted instructions of ranked-choice voting.

Meanwhile, San Francisco’s 2004 ranked choice voting revealed that the “prevalence of ranking three candidates were lowest among African Americans, Latinos, voters with less education, and those whose first language was not English.”[9] When individuals leave columns blank on their ballots, and the candidates they vote for are eliminated from contention, this leads to ballot exhaustion. Hence, ballots are not counted. Overall, the complicated nature of ranked choice voting can disenfranchise voters and render their votes void in the electoral process.

Common Fallacies of Proponents of Ranked Choice Voting

“Candidates need a majority to win”

Ranked choice advocates claim that it ensures that candidates need a majority of votes to win. Theoretically, this sounds correct, but there have been examples of candidates winning without securing a majority vote due to ballot exhaustion, such as during Maine’s 2018 Second Congressional Election.[10]

A 2014 study revealed that in 96 ranked choice races from across the country where additional rounds of tabulation were required to declare a winner, the eventual winner failed to receive a true majority 61 percent of the time.[11] Furthermore, the same study found ranked choice voting changed 17 percent of the outcomes — meaning the top vote receiver in a plurality has the potential of losing in ranked choice scenarios. Therefore, not only does ranked choice voting not always produce a majority, it can also distort election results, not reflecting the will of the citizenry.

“Ranked choice voting will increase voter turnout”

Advocates also claim ranked choice could improve America’s low level of voter participation, allowing voters a chance to make their voices heard. However, theory is one thing, reality is another. Empirical evidence tends to show that ranked choice voting “slightly depresses turnout relative to plurality elections.”[12] Because the evidence is not definitive, it is reckless to make such an ambitious claim that ranked choice voting results in increased voter turnout.

“Ranked choice voting will lead to more civility and less negative campaigning”

In a ranked choice system, candidates will be forced to appeal to a wider audience, and not alienate potential voters because they are battling for second place on the ballot. Doing so, hypothetically, would discourage candidates from running negative campaigns to garner more universal support. However, ranked choice didn’t decrease the volume of negative campaigning; the total number of independent expenditures in opposition to a candidate actually increased. The negativity was simply funded by outside groups rather than the candidates themselves.

Before Maine adopted the voting system in 2016, the 2006, 2010 and 2014 gubernatorial elections had zero independent expenditures in opposition to candidates. From 2014 to 2018, support expenditures decreased by more than 40 percent while opposition expenditures increased from $0 to $207,500.[13] A similar phenomenon occurred in Maine’s 2018 Second Congressional District election, with opposition expenditures increasing by 341 percent within the same period.[14]

Ultimately, a ranked choice system rewards candidates who avoid clear, principled positions and instead seek to be voters’ second or third choices. Candidates who are explicit about their beliefs often benefit from that clarity in the current, plurality system because they can attract a dedicated following. In a ranked choice, however, they risk alienating voters and therefore being ranked last. The politicians who succeed are those who either have few core beliefs or who are artful in concealing them. That means elections fail to yield mandates for governing, and there is a risk that the “leaders” they produce will be susceptible to the influence of powerful special interests.

Conclusion

Theoretically, a ranked choice voting system sounds attractive, but in reality, it creates a lot more problems than it solves.

To enforce fair and free elections, Connecticut does not need a complete overhaul of its current system. To bolster the plurality system’s integrity, Connecticut legislators must make voting less susceptible to fraud, and more inclusive. One easy way to combat fraud and coercive voting is by introducing a witness requirement. That is a rule requiring a voter to have another individual witness the voter filling out his or her ballot and attesting under legal penalty that the voter completing the ballot is the person to whom the ballot is registered.[15]

Nor does Connecticut require photo IDs to vote. Rather, one only needs to present a form of government ID that includes one’s name. Connecticut should provide all citizens of voting age with photo IDs to combat potential fraud and maximize voter turnout. Every voting-age citizen should have access to a photo ID.

In the last decade or so, Connecticut has introduced same-day voting registration, as well as automatic registration whenever someone interacts with Connecticut’s Department of Motor Vehicles. If Connecticut is serious about election integrity, it should continue to adopt policies that expand voter turnout while simultaneously ensuring that voters have confidence in every election’s outcome.

Central to the franchise is a dedication to ensuring that every vote counts. Whatever its flaws, that is the intent of the current plurality system — and it is a commitment worth keeping. From the foreseeable disenfranchisement of certain voters to ballot exhaustion to the creation of distorted, false majorities, ranked choice voting is rife with difficulties.

The plurality system is both a more efficient and more democratic system of voting. It must be reformed, not replaced.

Footnotes

[1] https://fairvote.org/our-reforms/ranked-choice-voting-information/

[2] https://lwvpdx.org/how-ranked-choice-voting-works/

[3] Alaska Policy Forum, “The failed experiment of ranked-choice voting: A case study of Maine and analysis of 96 other jurisdictions,” Alaska Policy Forum (2020), https://alaskapolicyforum.org/2020/10/failed-experiment-rcv/.

[4] https://ballotpedia.org/Ballot_exhaustion

[5] The failed experiment of ranked-choice voting: A case study of Maine and analysis of 96 other jurisdictions”, at 3.

[6] Oliphant, J. Baxter. “Many Voters Don’t Know Where Trump, Clinton Stand on Issues.” Pew Research Center. September 23, 2016. https://www.pewresearch.org/facttank/2016/09/23/ahead-of-debates-many-voters-dont-know-much-about-where-trump-clinton-standon-major-issues/.

[7] “Voting in Maine’s Ranked Choice Election.” Town of Wiscasset. 2018.

https://wiscasset.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/originals/rankchoicevoting.pdf

[8] RangeVoting.org “Spoilage and error rates with range voting versus other voting systems.” The Center for Range Voting (2019), https://rangevoting.org/SPRates.html.

[9] Neely, Francis, Lisel Blash, and Corey Cook. “An Assessment of Ranked-Choice Voting in the San Francisco 2004 Election Final Report.” FairVote. May 2005. http://archive.fairvote. org/sfrcv/SFSU PRI_RCV_final_report_June_30.pdf.

[10] “2018 Second Congressional District Election Results.” Maine Secretary of State. 2018. https://www.maine.gov/sos/cec/elec/results/2018/updated-summary-report-CD2.xls.

[11] Burnett, Craig M., and Vladimir Kogan. “Ballot (and Voter) “exhaustion” under Instant Runoff Voting: An Examination of Four Ranked-choice Elections.” Electoral Studies. November 18, 2014.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261379414001395.

[12] “The failed experiment of ranked-choice voting: A case study of Maine and analysis of 96 other jurisdictions”, at 16.

[13] “Candidate Elections.” Maine.gov. https://www.maine.gov/ethics/candidates/ disclosure.

[14] The failed experiment of ranked-choice voting: A case study of Maine and analysis of 96 other jurisdictions”, at 14.

[15] https://ballotpedia.org/What_methods_do_states_use_to_prevent_election_fraud%3F_(2020)