A new study shows Connecticut has become an even more burdensome state for would-be workers to obtain an occupational license for lower-income jobs.

Last month, the Institute for Justice (IJ), released the third edition of its “License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing” report that analyzed the burdens and scope of licensing across all 50 states and the District of Columbia for 102 lower-income occupations like barbers, cosmetologist and home entertainment installers. The previous edition was released in 2017. Burdens are measured by evaluating fees, education and experience, exams, minimum grade completed in school and minimum age.

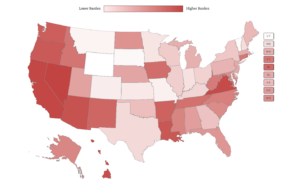

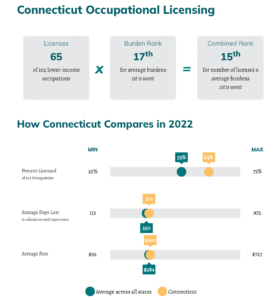

Connecticut ranked the 15th most burdensome state, as the most burdensome state with Nevada claiming the top spot. The state’s burden rank worsened four spots from the previous report since it created two new licenses for manicurists and skin care specialists. Of the 12 states that added licenses, only Connecticut and Virginia added more than one. No licenses were removed.

When compared to neighboring states, Connecticut fared worse than Massachusetts and New York, while Rhode Island ranked higher (11th), the worst in the northeast. Meanwhile, Vermont ranked as the least restrictive state in the nation.

Out of the 102 occupations studied, Connecticut requires 65 to have licenses — or 64 percent — exceeding the 53 percent average across all states. Louisiana had the most occupations licensed with 77; Wyoming was the least with 26. Additionally, the Constitution State fared worse than national averages in days lost to education, experience and exams (374 vs. 350); and average fees ($290 vs. $284). Fees include charges for application review and license issuance, exams, background checks, credit reports and fingerprinting.

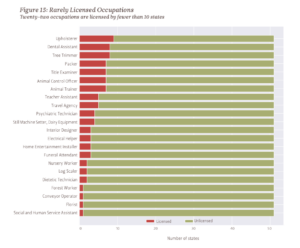

Most of the occupations listed in the study are not licensed universally meaning workers are safely practicing them in at least one state — and often many more than one — without getting permission from the government. Twenty-two occupations are licensed by fewer than 10 states. Connecticut has requirements for 5 of them: upholster, tree trimmer, animal trainer, forest worker and home entertainment installer.

The study finds “too many licensing burdens are excessively onerous or entirely unnecessary,” adding that “this red tape forces aspiring workers to waste time and money or, worse yet, shuts them out of work.”

The study’s authors argue that licensing requirements do not appear to be rationally related to public health and safety. For example, to become a home entertainment installer in Connecticut the aspiring worker must complete 900 hours of education while an emergency medical technician (EMT) only needs to complete 150 hours.

However, Connecticut took a step in the right direction last year to help eliminate some of its licensing barriers by passing a bill that loosened restrictions on those workers with prior felony convictions. They are no longer held captive by the crimes they already paid for.

To his credit, Gov. Ned Lamont supported legislation that would have allowed military spouses and people moving into the state to be licensed in Connecticut, provided they are in good standing, pay appropriate fees, and pass a state exam and background check. Lamont said, “No Connecticut resident who dreams of a good job with good wages should be denied the opportunity” adding that, “no skilled worker who wants to come live in Connecticut should get turned away on a technicality.”

The bipartisan bill received support from American Civil Liberties Union, the Office of Military Affairs, independent contractors and business associations. But in the end, the labor unions put a stop to the bill citing Koch Brothers conspiracy theories.

With the 2023 legislative session starting in less than a month, lawmakers have an opportunity to remove many of these regulatory barriers and boost economic growth. In the cases where licensing is appropriate for professions where health and safety are a concern, the General Assembly should take another pass at improving mobility and allow licenses to be portable from other states.

In instances where licensing is unnecessary and even harmful to workers, lawmakers should call for a full review of all current occupational licensing regulations and repeal those that other states do not require. Any new licensing should be rejected if not well supported by evidence proving it is necessary to protect public health and safety.