INTRODUCTION

About 124,000 Connecticut government employees belong to a labor union.[i] These include teachers, state agency employees, police officers and other municipal workers.

Unlike their private-sector peers who operate under federal law, most public-sector union members bargain under state laws (the exception being federal employees).

These unions are given extraordinary privileges under three Connecticut laws which, among other things, require public employers to collect millions of dollars in dues on their behalf.

Connecticut’s a union financial disclosure law (§31-77) provides an important protection to government employees, requiring labor organizations with at least 25 members to give members a detailed annual financial report of how their dues are spent.

These safeguards originally extended to all union members in both the public and private sectors, but the federal government preempted state law in 1959 with its own reporting standards for private-sector workers who bargain under the National Labor Relations Act. If a union does not represent anyone in the private sector, it is exempt from the federal law and instead subject to §31-77.

The state Department of Labor (DOL) has not been enforcing §31-77 for some time. It’s not clear why the agency lapsed in this responsibility – but it is important that this oversight end, and proper oversight resume.

BACKGROUND

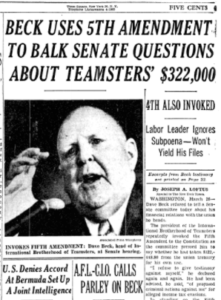

The financial operations of labor unions came under the national spotlight in mid-1950s, leading the U.S. Senate to empanel the Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management in January 1957, with a focus on the International Brotherhood of Teamsters.[ii]

The televised hearings saw the committee’s chief counsel, future Attorney General and U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy, grill Teamsters president David Beck about matters including $322,000 ($3.4 million in 2022 dollars) missing from the union treasury.[iii]

At the time, there were no federal regulations pertaining to union finances, leaving the matter to the states. Members of the Connecticut General Assembly had already been examining the need for such rules before the hearings, but the hearings elevated the issue significantly.

Connecticut lawmakers that year responded by adopting a measure to require unions to share information with their members and keep copies of their reports on file with the Secretary of the State.[iv]

The legislation passed with support from the Connecticut Federation of Labor and other unions.[v] As bill sponsor Representative John Lupton of Weston told the Labor Committee:

We have had shown to us over the past fifty years the necessity for regulations of this type in the commodity exchanges, in business in general and even in government itself. I can think of no place where there is greater propriety to the reasonable regulation of financial resources than in connection with union funds, because, after all, the source of the union treasury is the dues paid by the individual working man and where in our public and semi-public organizations in our country today should there more properly be public knowledge and particularly knowledge on the part of those who make the contributions, than this area here, where the working men and women of our country are contributing funds from their wages and salaries.[vi]

During the floor debate, the reporting requirement was framed in part as a compromise measure. Some lawmakers, citing the Teamsters hearings, pushed unsuccessfully for a right-to-work law that would shield workers from being forced to pay a union as a condition of employment.

Connecticut’s union financial disclosure law (§31-77) was eventually signed by Governor Abe Ribicoff. It required unions with at least 25 members to provide them with an annual financial report, and make a copy available for inspection by members at the Secretary of the State’s office, as well as authorizing the Secretary of the State to conduct audits at the request of union members. Failure to comply with the reporting requirement subjected unions to a $25 fine ($263 in 2022 dollars).

In 1971, the General Assembly transferred jurisdiction to DOL,[vii] and a subsequent opinion from then-Attorney General Joe Lieberman reaffirmed DOL’s authority to conduct union audits.[viii] As late as 1988, the General Assembly was making technical changes to the statute.[ix]

Connecticut’s law is in no way unique. Other states, including Hawaii (by many measures the country’s most unionized), adopted similar rules to deter misconduct.[x]

In 1959, the U.S. Congress eventually passed the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA, pronounced la-MARE-da), which among other things required most labor unions to file annual financial reports. Soon after, the General Assembly exempted unions covered by LMRDA from the state requirements.

LMRDA, however, did not apply to union members who work for the government and don’t bargain under federal rules. These workers instead negotiate contracts under state laws.

The interplay between federal and state reporting has sparked confusion at some of the highest levels of government. It’s crucial that the law’s function and original purpose be better understood.

CT’S OVERSIGHT

State records indicate DOL was enforcing §31-77—collecting annual reports—as late as 1993.[xi]

It’s unclear what led to the lapse. DOL experienced a bumpy transition between the Weicker and Rowland administrations in 1995, which may have disrupted lower-profile agency functions. In the mid-1990s, DOL leadership was also consumed with a botched effort to update its unemployment insurance software, which was ultimately abandoned in 1996.

State Labor Commissioner Sharon Palmer was quizzed about the reporting requirements during a February 2014 hearing and indicated DOL would seek to bring unions into compliance.[xii] As Representative Peter Tercyak later remarked on the House floor, “we had no trouble saying it’s time to start collecting those reports.”[xiii]

A group of representatives raised the issue in 2015 and proposed increasing the fines for noncompliance.[xiv]Their proposal did not receive a vote.

DOL said last year it did not possess any financial records collected under §31-77.[xv] The agency separately told at least one public employee who requested access to union records that they were unavailable.

Then-Acting State Labor Commissioner Danté Bartolomeo was asked about the law during her February 2022 confirmation hearing. Bartolomeo raised concerns about the “redundancy” of §31-77, arguing that it was “duplicative of what’s sent in to the feds.”[xvi]

Bartolomeo also said DOL had received few requests for the related financial reports, though the Department also does not appear to have undertaken any effort in recent years to educate union members about the protections they (theoretically) enjoy under §31-77.

As explained above, however, the worker protections granted by §31-77 apply only to public employees who aren’t protected by the federal LMRDA, because the General Assembly in 1961 deliberately removed the state mandate on any union covered by LMRDA.

DOL this year separately asked the General Assembly to repeal §31-77 as part of a package of “technical” changes, characterizing the law as “obsolete.” The request was rejected by the Labor & Public Employees committee.

WHY IT MATTERS

Connecticut public employers—state government, municipalities, and school districts–annually collect approximately $50 million in dues on behalf of public employee unions (ironically, the exact figure is unknown because §31-77 is not enforced). It is difficult to imagine any other instance where the government would be involved in a transaction of this scale without developing and enforcing an accountability mechanism to verify the money is being spent appropriately.

For instance, political campaigns that receive public money through the state’s Citizens’ Election Program must document how each dollar is spent—and are subject to state audit. Connecticut also imposes extensive financial disclosure requirements on charities operating in the state.

The need for such safeguards in Connecticut’s government labor space is apparent at multiple levels.

- The trio of state laws that authorized collective bargaining by Connecticut government officials—the State Employee Relations Act, the Teacher Negotiation Act, and the Municipal Employee Relations Act—were adopted when §31-77 was not only already on the books but being actively enforced. That is to say, the General Assembly built the current collective bargaining framework on the assumption that this accountability mechanism would keep functioning.

- The state Board of Labor Relations has ruled that it is “protected activity” under the State Employee Relations Act for union members “to criticize the honesty, competence or financial practices of union officials.”[xvii]31-77 plays a necessary role in enabling union members to exercise those rights.

- Connecticut labor officials and judges adjudicating state public-sector labor matters routinely look to the National Labor Relations Act, where an even more expansive reporting regime operates.

The state itself has an interest in protecting union members from financial impropriety because the General Assembly has made state and local agencies a party to any potential misconduct by forcing them to act as fiscal intermediaries between the unions and their members. State and local officials are prohibited from exercising any discretion over whether to surrender the union dues they collect and would face sanctions if they hesitated to hand over the money.

In fact, the General Assembly doubled down on this policy last year by making it more difficult for union members to stop paying dues, even if they suspect union funds are being stolen.[xviii]

As a practical matter, the reporting requirement would likely deter financial malfeasance—if it were enforced.

At least 11 Connecticut union presidents and treasurers have been criminally charged for financial crimes committed against their unions since 2005. Union members working in places ranging from the Cheshire police department to Region 18 schools to the state prison system, and others, have had officers steal from them over the past eight years. One Newtown police union official was charged in 2012 with stealing over $180,000 from members.[xix]

Unions occasionally cite reporting and audit rules in their own bylaws or constitutions, though these are by no means uniform. The organizations sometimes handle these matters internally without notifying law enforcement—or members.

Although some locals are affiliated with larger unions and must comply with internal annual reporting rules, many are not. This has created an environment that requires careful attention by the General Assembly. Proper enforcement of §31-77 would have likely allowed the thousands of union members touched by financial crimes in recent years to uncover misconduct sooner or possibly prevented it altogether.

Just across the border, there have been even more pronounced reminders about why this law matters: the head of the NYPD sergeants’ union (the country’s fifth-largest police union) was arrested earlier this year on allegations he stole over $1 million from his union over four years.[xx] New York doesn’t have reporting requirements, and the matter did not become widely known to members until the FBI raided the union’s office. Teachers in the Auburn school district, outside Syracuse, didn’t learn that their local president had stolen more than $800,000 from them until after she died.[xxi] These were just a few of at least 40 instances since 2010 in which a New York union official has been criminally charged with financial crimes related to their his or her role.

As long as state law requires government agencies to deduct union dues, it must ensure this is happening responsibly.

OVERDUE ACTIONS

The reporting requirements in §31-77 are a cornerstone of public-sector collective bargaining in Connecticut. State and local officials should take the following steps to make sure the policy functions as intended:

- DOL should immediately set a timeframe for all unions to come into compliance, and should promulgate regulations to allow the unions to submit documents electronically to minimize costs;

- the General Assembly should revisit §31-77, as Commissioner Bartolomeo suggested, and re-evaluate the decades-old fine structure; and

- all state and local public employers, including towns, cities, and school districts, should notify their unionized employees about their §31-77 rights.

As an alternative, the General Assembly could re-evaluate the practice of forcing public employers to collect union dues in the first place. The state’s interest in exercising oversight would decrease significantly if the unions had a direct customer relationship with their members—as payment technology readily allows—and government resources weren’t used to collect money on their behalf.

[i] Hirsch, Barry & David Macpherson, “Union Membership, Coverage, Density and Employment by State, 2021,” Union Membership and Coverage Database from the CPS, UnionStats.com

[ii] “About Investigations | Selected List,” United States Senate. senate.gov/about/powers-procedures/investigations/select-investigations.htm

[iii] Loftus, Joseph, “BECK USES 5TH AMENDMENT TO BALK SENATE QUESTIONS ABOUT TEAMSTERS’ $322,000,” New York Times, 27 Mar 1957.

[iv] PA 628 of 1957

[v] Senate transcript, CT General Assembly, 28 May 1957, p.3495

[vi] Labor Committee transcript, CT General Assembly, 16 Apr 1957, p.616

[vii] PA 77 of 1971

[viii] Opinion 84-68, Office of the Attorney General, June 15, 1984

[ix] PA 88-364

[x] Hawaii Rev. Stat. §89-15

[xi] Decision No. 3175, Connecticut State Board of Labor Relations, 13 Jan 1994. ctdol.state.ct.us/csblr/decisions-pdf/1994/3175.pdf

[xii] Labor & Public Employees Committee transcript, CT General Assembly, 18 Feb 2014

[xiii] House transcript, CT General Assembly, 2 May 2014

[xiv] HB 5876 of 2015

[xv] Fitch, Marc, “Connecticut law requires unions to file annual reports with DOL but it’s not enforced,” Yankee Institute, 22 Sep 2021. yankee-institute-dev.10web.me/2021/09/22/connecticut-law-requires-unions-to-file-annual-reports-with-dol-but-its-not-being-enforced

[xvi] Executive and Legislative Nominations Committee Meeting and Hearing for DPH, DOL, and DMHAS Commissioners, CT-N, 24 Feb 2022. ct-n.com/ctnplayer.asp?odID=19411

[xvii] Decision No. 2464, Connecticut State Board of Labor Relations, 19 Mar 1986. ctdol.state.ct.us/csblr/decisions-pdf/1986/2464.pdf

[xviii] PA 21-25

[xix] Pirro, John, “Ex-Newtown police union head sentenced,” CT Post, 2 May 12. ctpost.com/default/article/Ex-Newtown-police-union-head-sentenced-3529671.php

[xx] “Former President Of Law Enforcement Union Edward Mullins Charged With Defrauding Union And Its Members,” US DOJ, 23 Feb 22. justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/former-president-law-enforcement-union-edward-mullins-charged-defrauding-union-and-its

[xxi] Hannagan, Charley, “Union leaders: former Auburn Teachers Association president used $800,000 in union funds for gambling, trips,” Post-Standard, 22 Apr 2013. syracuse.com/news/2013/04/union_leaders_former_auburn_te.html