A panel of experts argued that healthcare provider consolidation through hospital mergers and private equity takeovers are limiting competition in the health care industry and driving health care prices higher, during an online informational forum hosted by Connecticut’s Insurance and Real Estate Committee Co-Chair Rep. Kerry Wood, D-Rocky Hill.

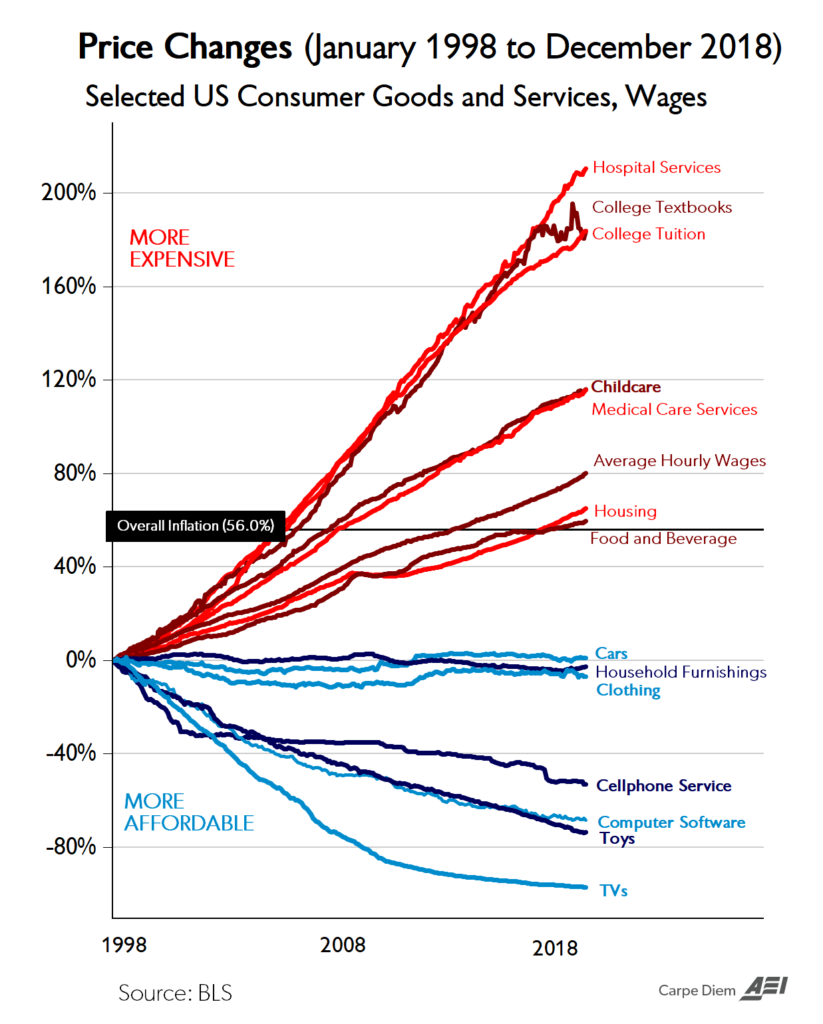

Healthcare costs have risen dramatically over inflation during the past two decades, even as many other products and services have declined in cost.

If the price of milk had risen at the same rate as health care prices since World War II, a gallon at the store would cost $160, according to a presentation by Katherine Gudiksen, Ph.D, from The Source on Healthcare Price and Competition, part of the University of California Hastings College of the Law.

“Prices are the primary reason why the U.S. spends more on health care than any other country,” Gudiksen said.

Gudiksen and Laura Anderson, vice-president of policy at the American Antitrust Institute, focused on mergers of health care providers – whether between hospitals or hospitals acquiring private physician practices – that give those companies massive market share, decrease competition and then drive-up prices, sometimes at the behest of private equity firms.

Gudiksen noted that post-merger hospital prices increased from 20 to 44 percent, mergers of hospitals with independent physician practices increased prices an average of 14 percent and mergers with clinics increased prices upwards of 44 percent.

The mergers and growing market shares also allow healthcare companies demand “all or nothing” insurance network coverage, forcing the insurer to cover all the company’s facilities or none of them and can limit insurance companies’ attempt to steer individuals toward high value, low-cost options.

Essentially, the experts argued, lack of antitrust enforcement at the state and national level have allowed healthcare companies and private equity firms to usurp the competitive free market which tends to keep costs lower.

As the size of a healthcare company grows, it gives them more leverage to set prices and rates that insurance companies must pay.

“There are two failures that have allowed prices to increase so fast,” Gudiksen said. “The first is a failure to protect competition and rigorously enforce anti-trust laws and the second is a failure to act when the competitive forces in the market are no longer sufficient to constrain these price increases.”

The presentation also covered the cost of prescription medication costs, which in the United States are largely set by the pharmaceutical companies, as opposed to European countries that use rate setting to determine prescription drug prices.

“Compared to citizens of other countries, Americans pay a lot more for prescription drugs,” said Drew Gattine of the National Academy for State Health Policy. “The rise in cost of prescription drugs is a huge driver in the overall increase of healthcare costs that Americans experience routinely.”

“When it comes to prescription drugs, the United States has a very complicated payment and distribution system that begins with the prices set by the manufacturer,” Gattine said.

The rapidly rising prices are spurring calls for government intervention at both the national and state level, but how the government should intervene is up for debate.

In Connecticut, State Comptroller Kevin Lembo and progressive lawmakers have focused on insurance companies, pushing for a state public option plan that would allow individuals and groups to purchase health insurance through the state’s healthcare plan – a proposal vigorously opposed by Connecticut’s flagship insurance industry.

The public-option health care bill failed during the 2021 legislative session after it was altered in committee and Gov. Lamont threatened to veto the bill amid outcry by Connecticut insurance companies and some unions like the Teamsters who maintain their own healthcare plans.

Republicans offered an alternative to the public health option, saying the state should use the reinsurance program allowed by the Affordable Care Act, healthcare cost benchmarking used by states like Massachusetts and getting prescription drugs from Canada.

The expert speakers offered some policy suggestions that have been utilized by other states.

Those policy suggestions included greater oversight of hospital mergers and private equity investments in healthcare facilities, using international reference rates for the most expensive prescription drugs paid for by the state healthcare plan, allowing states to review and institute penalties for unsupported drug price increases and establishing price benchmarks.

Roman Alder MD

October 30, 2021 @ 9:45 pm

The antitrust division of the attorney general office and the office of health strategy, both have ignored the formation of a regional medical monopoly called nuvanc health. A certificate of public advantage should have been in place in 2019. Nuvance health has abused is market position as a regional monopoly with unrestrained pricing power