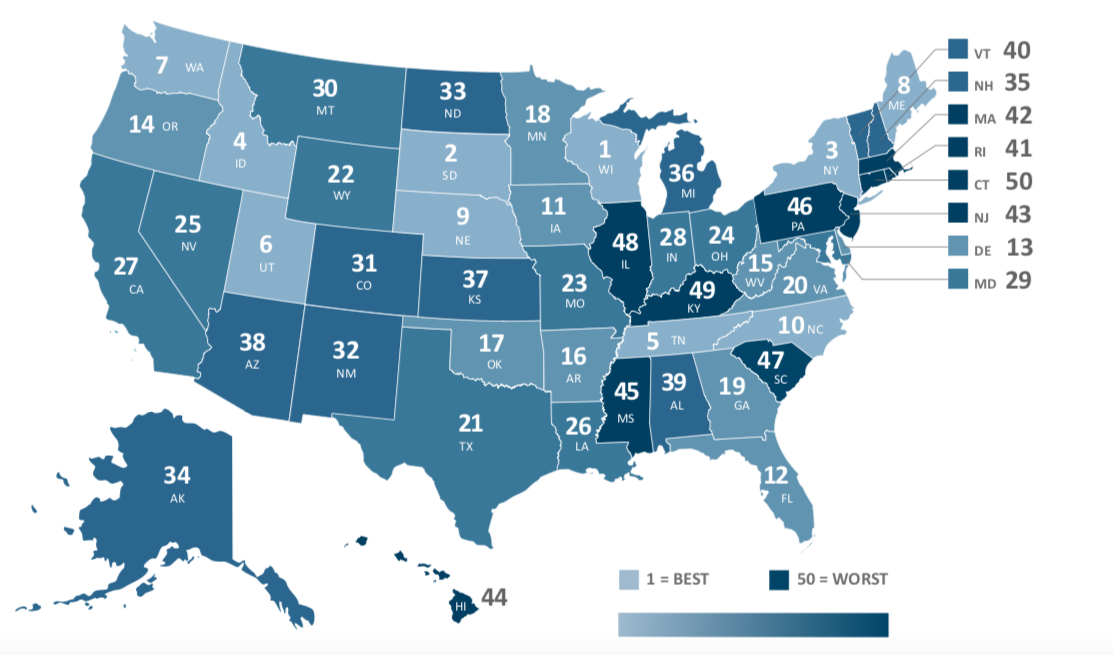

Connecticut has the worst-funded pension system in the country, according to a new annual report released by the American Legislative Exchange Council.

Using a “risk free” discount rate – which increases the state’s estimated pension debt – ALEC found that Connecticut only had 23.8 percent of the funds necessary to meet its $111.2 billion in unfunded pension liabilities.

Overall, across all fifty states, unfunded pension liabilities totaled $5.8 trillion, an increase of $900 billion over their previous year’s report, largely due to quickly growing pension debts in states like California, Illinois, Texas and Massachusetts.

Connecticut’s total unfunded pension debt was the 36th highest in the country and 48th on a per capita basis, according to the report.

However, there are several differences between ALEC’s report and what the state of Connecticut reports as its pension debt, largely because of the assumptions made in calculating the unfunded pension liability.

According to Connecticut’s 2020 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, the state’s unfunded pension liabilities for state employees, teachers and judges sits at roughly $40 billion.

And according to 2020 state reports for Connecticut’s two largest and most unfunded pension systems, the State Employee Retirement System is 35.8 percent funded, while the Teachers Retirement System is 51.3 percent funded.

Those figures, however, assume the state will get 6.9 percent annual return on its pension investments. ALEC, on the other hand, used a risk-free discount rate of 2.34 percent based on the yield of U.S. Treasury bonds, which causes the unfunded liability to rise dramatically.

Connecticut has been making some positive pension changes in recent years, however, lowering its assumed rate of return from 8 percent to 6.9 percent and instituting the volatility cap, which, after fully funding the state’s Rainy Day Fund, allows the state treasurer to pay off some of Connecticut’s pension debt.

Under the latest budget agreement signed by Gov. Ned Lamont, Connecticut will pay roughly $1 billion toward the pension debt.

According to ALEC’s report, Connecticut’s pension funding ratio increased by 9.3 percent, while states like California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, North Carolina and Pennsylvania saw their funding decrease. Vermont’s pension funding decreased by over 20 percent, according to the study.

Under agreements made by both Gov. Dannel Malloy and Lamont, Connecticut extended the payoff dates for Connecticut’s unfunded pension liabilities, pushing the payoff period into the mid-2040s to avoid costs potentially spiking to unsupportable levels, but also adding billions to the debt.

Connecticut also instituted a fourth retirement tier for new employees that incorporates a pension/defined-contribution hybrid plan and limits the amount of overtime that can be applied to pension calculations as part of the 2017 SEBAC Agreement. In exchange, state employees were granted pay raises and layoff protections.

Connecticut’s long-term pension problems have essentially caught the state in a Catch-22 and this year’s payoff may be the last for the foreseeable future.

Connecticut balanced its budget this session with a massive influx of federal COVID-relief funds, helping close a budget deficit, but the next biennium is projected to face a multi-billion dollar deficit as well and may require Connecticut to either raise taxes, implement spending cuts or use its reserve funds to bridge the gap.

The deposits into the Rainy Day Fund are based on the volatility cap, which is tied to investment earnings. Since the imposition of the state income tax, Connecticut has become more and more reliant on the wealthiest taxpayers who receive much of their income from Wall Street investments that are notoriously volatile.

That reliance can mean feast or famine for Connecticut, while the state’s pension payments have made a steady upward migration.

Although pension payments are projected to flatten out over the next several years – provided Connecticut meets its investment returns – a downward shift in the stock market could leave Connecticut’s paying more for its pensions with less revenue.

Connecticut’s pension debt is tied to a myriad of cost issues facing state government. This trickle-down effect has caused funding problems statewide, resulting in higher student tuition for public colleges and universities, the loss of university research grants, and fringe benefit costs that nearly double the price of hiring even a single state employee.

Connecticut’s status as having the most underfunded pension systems in the country is not new. Previous pension studies by ALEC also found Connecticut to be in the worst shape when it comes to pension funding. Although, the numbers have changed year-over-year, the result has remained the same.

In ALEC’s 2017 study, Connecticut’s pension debt was estimated at $127 billion – $16 billion more than their recently-released study – and had a funding ratio of 19 percent.

Wisconsin ranked top in the nation for its pension funding based, in part, over its risk-sharing plan that requires the state to split the annual pension contribution with pension plan participants.

The study authors recommended that struggling states reform their pension systems through implementing defined-contribution plans or risk-sharing plans and to avoid pension investments based environmental, social and governance principles, known as ESG, which are shaped by political leanings.

Pension reforms for Connecticut state employees, however, require approval by the State Employee Bargaining Agent Coalition. Teacher pensions, conversely, are set in state statute and can be changed legislatively, but those changes generally come with a heavy political price-tag.

Jay Koolis

July 29, 2021 @ 12:06 pm

The basIs of this analysis is ludicrous and completely negates its findngs. Assuming a 2.34 rate of return is unrealistic at best. The fact that your organization keeps promoting highly biased and questionable analyses shows your complete lack of objectivity and reason. I’ve seen this repeatedly in so called analyses your organiZaTIon publishes. That, in my opinion, negates anything your organization Reports and serves no one but the special interests your organization promotes.

Im not sure why but i cannot turn off the all caps in this fIeld. You might want to check that.

Mario

September 7, 2021 @ 12:37 pm

UMmm…. Connecticut is bankrupt!!!🤔

PIBERMAN

September 28, 2021 @ 11:17 am

CT DEMS HAVE OTHER INTERESTS.

Daniel Cole

November 8, 2021 @ 5:08 am

i have a solution…..how about taxing those public pensions at 50% since teachers and state workers contributed so little to them in the first place…they’re contribution rate from their paycheck should be at least 20% when u look back at what they’re getting in return for retirement…..but that would require leadership from Gov Lamont which he lacks