The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College issued a report on the pandemic’s effect on state and municipal pension systems and listed Connecticut’s State Employee Retirement System as one of the ten worst-funded pension plans in the country.

The report projected SERS would see a 4.6 percent decline in funding due to the pandemic and economic downturn because the pension system will likely see negative investment returns.

CRR was influential in the decisions of Gov. Dannel Malloy and Gov. Ned Lamont to re-amortize Connecticut’s pension systems for both state employees and teachers after they predicted massive cost increases in a 2015 report.

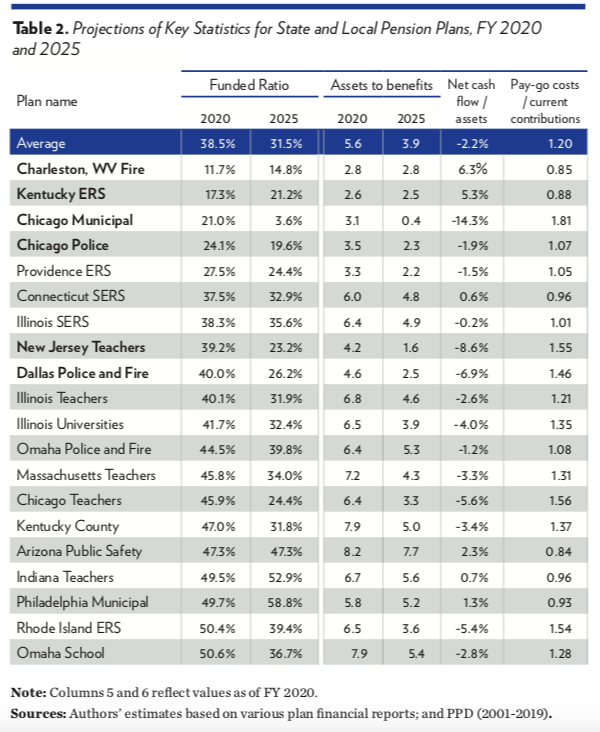

Connecticut’s SERS system was listed as the sixth-worst funded public pension plan in the country and was only 37.5 percent funded. However, the decline of the markets in response to the COVID-19 pandemic will leave the pension fund only 32.9 percent by 2025, according to CRR’s report.

“If markets remain at their current levels until June, most public pension plans will conclude the fiscal year 2020 with negative annual investment returns, reduced asset values, lower funded ratios and higher actuarial costs,” wrote Jean-Pierre Aubry, Alicia H. Munnell and Keven Wandrei, authors of the report.

With June just around the corner, Wall Street has been a mixed bag since the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in March. With the initial shock and downturn of roughly 30 percent, the market has occasionally bounced upwards on optimistic news that a vaccine for the coronavirus is close at hand.

But the underlying factors of greatly reduced travel, the shutdown of businesses, record unemployment, a possible second-wave of the virus and an oil-price war have not changed. The market remains a roller coaster that is still far off from its previous highs.

The report did conclude that Connecticut would still have assets to pay for its pensions – unlike some major municipal plans like Chicago and New Jersey Teachers systems, which could run out of money within three years – but would face an increase in the annual payment.

“A decline in funded levels increases the actuarially determined contribution – the payment to keep the plan on a steady path toward full funding,” the report says.

Connecticut currently has $22.8 billion in unfunded pension liabilities for the state employee system and payments on that debt make up most of state’s $1.6 billion actuarily required contribution.

Connecticut’s annual payment to the SERS system was already expected to increase to more than $2 billion per year by 2023 and would not decrease until 2040, according to the fiscal analysis of the 2019 memorandum of understanding to re-amortize the payments.

However, those projections are based on some key assumptions outlined in the valuation of the plan, which includes an assumed long-term rate of return for market investments of 6.9 percent.

Connecticut had lowered the assumed rate of return for its SERS system from 8 percent to 6.9 percent when Malloy re-amortized the pension debt in 2017. Over the last ten years during a long-run bull market, Connecticut reached an 8.02 percent return rate, according to reports published by the Office of the State Treasurer.

But the ten-year return rate doesn’t include the 2008 and 2009 recession, which saw negative returns ranging from almost 5 percent in the first year to 18 percent in the second.

According to the Connecticut School and State Finance Project, since 2001 Connecticut has averaged a 6 percent rate of return.

According to CRR’s 2015 report on SERS, failing to meet the annual rate of return contributed $3.2 billion to the total unfunded liability between 2000 and 2014.

Connecticut had historically underfunded its state employee pension system, including through a series of SEBAC contracts with Gov. Lowell Weicker and Gov. John Rowland that overrode state law requiring the full annual payments to be made every year starting in 1986.

During that time, Connecticut’s unfunded pension liability has exploded – and so have the payments on that debt.

The 2015 report from CRR stated Connecticut’s unfunded liabilities for state employees was $14.9 billion. Five years later the debt now stands at $22.8 billion.

In 2015, Connecticut’s annual pension payment was $1.3 billion, according to state actuarial reports.

The latest re-amortization of the debt lowered the amount of the annual SERS contribution in the short-term but added roughly $3 billion to the total debt.

James McAuliffe

May 26, 2020 @ 12:15 pm

Actually, the unfunded SERS exploded in the Malloy years.

Donna McLaughlin

May 27, 2020 @ 10:59 am

That is very troublesome news for the people that collect pensios. How long will it be before there just is not enough to go around.