Republican Senate Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Kentucky, said on Wednesday he would rather see states declare bankruptcy than issue another $500 billion requested by the National Governors Association to bail out states facing lower revenues and skyrocketing debt costs.

“There’s not going to be any desire on the Republican side to bail out state pensions by borrowing money from future generations,” McConnell said on the Hugh Hewitt radio show.

Gov. Ned Lamont said McConnell was taking a “let them eat cake” approach to economic downturn’s effect on state finances during his Wednesday press conference.

Lamont said Connecticut is looking at a $500 million deficit for this fiscal year, which ends June 30, and says that 85 percent of that deficit is due to lower tax revenue and 15 percent is due to costs related to the state’s pandemic response that was not compensated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

The governor said the state has ample cash on hand to weather the pandemic for now. “We’re in good shape through this fiscal year,” Lamont said.

But states across the country are facing lower tax revenue and higher costs related to debt and responding to the pandemic.

“That’s why states are desperate right now,” Lamont said. “We’re not in that position.”

But, according to the Office of Fiscal Analysis, Connecticut has an ongoing “structural imbalance” that will only be exasperated by the pandemic and economic recession. Namely, fixed costs were growing faster than revenue.

Now, with Connecticut revenues set to take a big hit, that trend will only grow.

Connecticut currently has a $2.5 billion reserve fund and, according the Treasurer’s Office, another $1.5 billion in cash on hand, meaning Connecticut may be able to weather this recession even without a bailout from the federal government.

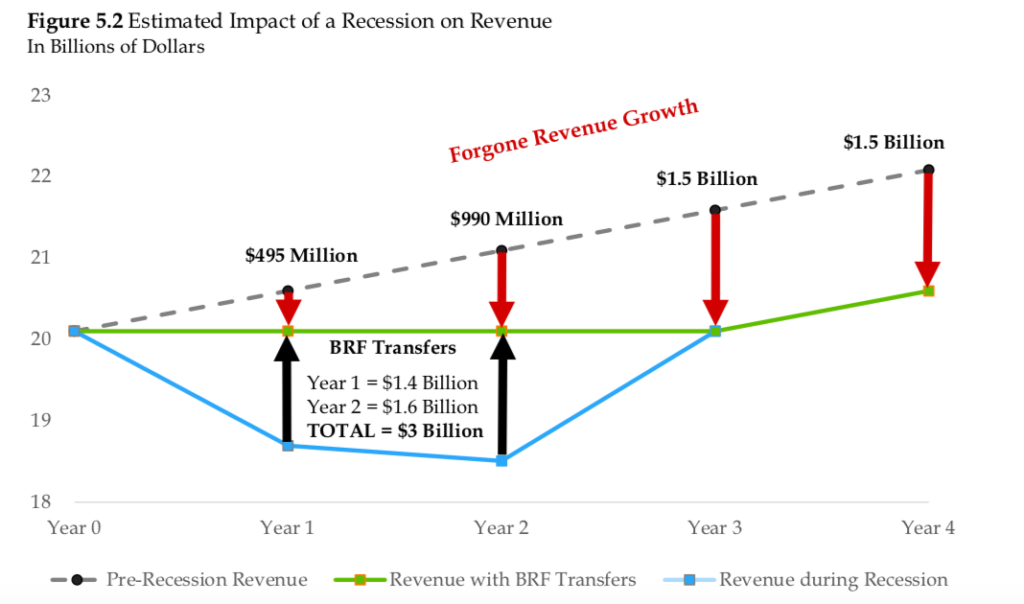

The cash reserves will only serve to keep Connecticut at current budget levels but the foregone projected revenue increases will take their toll on state finances for years to come.

An estimate from the OFA showed Connecticut would likely need $3 billion over two years to maintain revenue a pre-recession levels, but the long-term effect is $1.5 billion in forgone revenue, while fixed costs related to bond payments, pensions, retiree healthcare and Medicaid continue to grow.

“The forgone revenue growth has a permanent impact on the structural imbalance as fixed cost expenditures continue to grow while revenue remains flat for three years,” the OFA wrote in its Fiscal Accountability Report. “Enduring solutions will be needed to address this ongoing problem, which cannot be fixed through temporary measures like use of the budget reserve fund.”

The growth of fixed costs was outpacing state revenue increases by 2 to 1 before the pandemic and economic downturn.

The pandemic shutdown has had multiple effects on Connecticut finances, lowering both income tax revenue and sales tax revenue as thousands of retail stores, restaurants and other nonessential businesses have been closed to enforce social distancing.

During the 2008 recession, Connecticut saw a drop in the state income tax of $1.3 billion whereas the state’s sales tax revenue decreased only $300 million.

Total revenue declined $1.9 billion in one year and didn’t reach pre-recession levels until 2012 after Gov. Dannel Malloy passed a large tax increase in 2011.

But Connecticut faces a longer-term challenge from its underfunded pension systems, which will also be affected by the market downturn as the 6.9 percent rate of return — relied upon to ensure full funding of those pension systems — will not be met this year or probably next year.

Debt for the Teachers Retirement System increased from $6.5 billion in 2008 to $16.7 billion in 2018; debt for the State Employee Retirement System rose from $9.3 billion to $36 billion during the same time period.

Connecticut currently has $61 billion in unfunded pension and retirement healthcare liabilities, according to the state’s latest valuation reports, a nearly 68 percent increase over the state’s unfunded liabilities in 2008.

Connecticut had underfunded its pensions for decades. However, even as the state began to fully fund its teacher pensions in 2008 and its state employee pensions in 2015 — and as Wall Street experienced prolonged growth — the unfunded liabilities have only increased.

Debt for the Teachers Retirement System increased from $6.5 billion in 2008 to $16.7 billion in 2018; debt for the State Employee Retirement System rose from $9.3 billion to $36 billion during the same time period.

Add on Connecticut’s bonded debt, which is currently $32.9 billion, and state taxpayers are looking at over $100 billion in long-term debt and yearly payments that total $6.8 billion per year by 2024.

Donald Klepper-Smith, chief economist for DataCore Partners and former economic advisor to Gov. M. Jodi Rell, says that Connecticut’s debt is “simply not sustainable.”

“Connecticut had the third highest relative debt levels at 285 percent of source income as of 2018, and that was before the coronavirus,” Smith said.

“We’ve all been under the false impression that the perpetual rising levels of debt don’t matter,” Smith said. “At some point, though, the bill comes due and we all have to live within our means.”

That all may be easier said than done, however. Connecticut’s $22.8 billion in state employee pension debt and $17 billion in retiree healthcare debt is controlled by a 2007 contract between State Employee Bargaining Agent Coalition and the state of Connecticut.

That contract was renegotiated several times, most recently in 2017 when the unions and Gov. Dannel Malloy created a new retirement tier, increased pension contributions for current employees and increased healthcare copays for retirees to mitigate a massive state deficit.

In exchange, the SEBAC contract was extended until 2027 and state employees were awarded bonuses, raises – including a 5.5 percent increase this year — and layoff protections until 2021.

Nothing less than SEBAC returning to the negotiating table can alter the pension system until 2027, and, even if they did, it is unlikely they would give in to any major restructuring. Teacher pensions, on the other hand, are set by the legislature and can be changed by a vote.

States are not currently allowed to declare bankruptcy, however, in 2016 Congress passed a law to enable Puerto Rico to effectively declare bankruptcy. The move forced a restructuring Puerto Rico’s debt and placed the U.S. territory under the control of a panel of officials and financial experts.

Puerto Rico, at the time, had $74 billion in bonded debt and $49 billion in unfunded pension liabilities.

We’ve all been under the false impression that the perpetual rising levels of debt don’t matter. At some point, though, the bill comes due and we all have to live within our means.

Donald Klepper-Smith, Chief Economist for DataCore Partners LLC

But there is currently no law allowing states to effectively go bankrupt. When Illinois ran out of money in 2015 and couldn’t pass a budget, it was forced to not pay vendors – and even lottery winners – for a period of time before it could recover.

Cities – notably Detroit and Central Falls in Rhode Island – have also declared bankruptcy, forcing bond payments or pension and retiree medical benefits to be cut.

“There’s not one business in the state that would have committed to a lucrative labor contract of wages and benefits at the tail end of the longest business cycle in post-war history, but that’s exactly what the state of Connecticut did,” Smith said, labeling this “the worst recession dating back to World War II.”

But, at this point, any opportunity to fix that structural imbalance is gone and the state will likely face hard decisions in the coming years to make up for the loss of revenue and rising costs.

McConnell’s comment drew condemnation from other governors whose states also face massive debt and pension problems, including New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy.

Depending on the how the pension debt is measured, New Jersey is one of the few states – along with Illinois — in a similar position as Connecticut when it comes to long-term debt and unfunded pension liabilities.

Notably, McConnell’s own state of Kentucky also has one of the worst-funded pension systems in the United States, second only to Connecticut in a 2018 report by the American Legislative Exchange Council.

COVID

April 24, 2020 @ 11:42 am

Most importantly, the measures required Greece to reform its pension system. Pension payments had absorbed 17.5 percent of GDP, higher than in any other EU country. Public pensions were 9 percent underfunded, compared to 3 percent for other nations. Austerity measures required Greece to cut pensions by 1 percent of GDP. It also required a higher pension contribution by employees and limited early retirement. ? ?

SteveHC

May 16, 2020 @ 6:25 am

Greece is a country, not a state. And it had no choice but to make those cuts – and MANY others – because the only lenders available to it REQUIRED the country to make those cuts as a condition for provision of loans, grants, and forgiveness of certain debts.

In other words, apples to oranges…

Harry

August 31, 2020 @ 6:36 pm

You are right Steve on your reply about Greece. You are wrong though to think that several states are not headed in their same direction though… It is unsustainable and the only alternative is to allow states to go bankrupt and start over. The biggest issue upcoming on dealing with them is that the same people who write the laws also collect federal and state pensions….. I will say it again LET THEM GO BANKRUPT NOW… New York, California, Illinois, Kentucky and New Jersey…. ALL run by the Democrats except one…. If we in the private sector cannot collect social security / 401k until a minimum of 62 years of age then that is what applies to pensions also… I will NOT pay higher and higher taxes for the 100,000 dollar club of pensioners….

Jo

June 7, 2020 @ 9:19 pm

Connecticut Democrats made a deal with the devil. In order to buy votes from teachers and other employees they made retirement promises the can’t be met. They would rather bankrupt the state than give up power.

ERIC

January 21, 2022 @ 6:28 pm

I lived in connecticut in my early years and remember a state that had strong manufacturing, and an innate work ethic. I believe there was a nation-wide push to white collar jobs, and a disdain for hard working blue collar jobs IN THE LATE 1960’S. CONNECTICUT PUSHED THAT TO THE FORE, AND THAT WAS THE WRONG DIRECTION, i WILL NOT BLAME ANY POLITICAL PARTY AS THE PEOPLE OF EVERY u.s. STATE HAVE THE POWER TO DO WHAT IS IN THEIR BEST INTERST. iT IS A PITY THAT POLITICIANS HAVE THAT MUCH INFLUENCE, AND POWER TO ENRICH THEMSELVES, AND SH#T ON THE PEOPLE THAT PUT THEM THERE.