Connecticut’s two largest pension funds received 16 percent returns over the course of one year thanks to a surging stock market, giving the state a much needed boost.

High returns for the teachers’ pension fund and the state employees’ pension fund will likely lower Connecticut’s annual required contribution, a welcome helping hand as the state moves toward another budget year facing considerable challenges and a potential $4.6 billion deficit.

“This performance is especially needed at a time when the state is facing serious fiscal difficulties,” Connecticut State Treasurer Denise Nappier said in a press release. “When we perform above expectations, those gains can help trim the state’s pension contributions going forward.”

Nappier said the state’s diversified portfolio helped bolster the increase. Overall Connecticut’s pension fund return exceeded 70 percent of its peers, according to Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service.

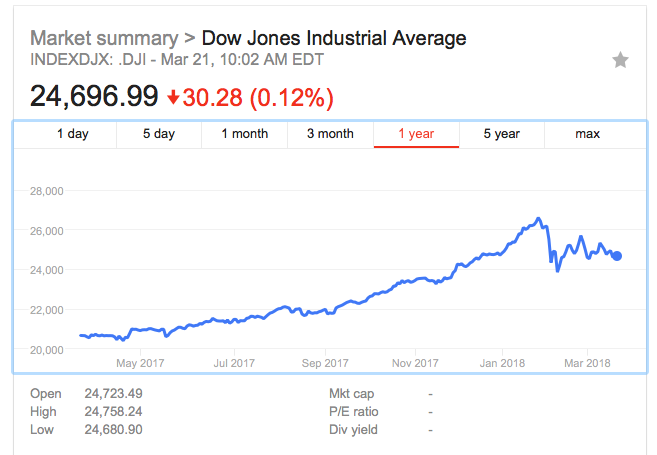

Year-to-date the Dow Jones has gained 19.4 percent with some occasional wild swings.

The stock market experienced rapid growth following President Donald Trump’s move to lower the corporate tax rate and roll back regulations, but also experienced some deep dives with the president’s announcement of tariffs on steel products.

Historically, Connecticut’s pension funds have returned less than the state’s assumed rate of return, which increases the state’s unfunded pension liability.

Until 2017, Connecticut applied an 8 percent discount rate to its state employee retirement fund. Gov. Dannel Malloy lowered the discount rate to 6.9 percent. Lowering the discount rate means the state has to contribute more toward the pension fund, but helps strengthen the system in the long-run by making more realistic assumptions.

As of 2016, the state employee retirement fund had only returned 5.25 percent annualized over 10 years, according the treasurer’s office and the teacher pension fund — which still assumes an 8 percent discount rate — had returned 5.14 percent.

Connecticut’s pension funds are among the worst funded in the nation and ranked dead last in an annual study by the American Legislative Exchange Council.

The state’s unfunded pension liabilities are one of the state’s fastest growing expenses and failing to meet the state’s discount rate adds to those costs. Contributions toward SERS will grow from $1.5 billion to $2.2 billion by 2027, after Malloy refinanced the state’s debt and stretched out payments until 2046.

The state’s teacher pensions threaten to grow even more, potentially reaching $6 billion per year if the state consistently fails to meet its discount rate, according to the Center for Retirement Studies at Boston College.

Nappier said previously she feels such a massive increase is unlikely, but even a moderate increase threatens the state’s budget at a fiscally perilous time for Connecticut.

Malloy’s restructuring of the state’s SERS payments and negotiation of the 2017 SEBAC concessions deal means Connecticut’s state employee pension issues are locked in place for the foreseeable future, but the same cannot be said of the teachers retirement system.

Unlike state employee pensions, teacher pensions are set in statute and can be changed legislatively. Part of the 2017 budget agreement included raising teachers’ pension contributions by one percent, but more drastic measures will likely be needed to prevent the costs from reaching unsupportable levels.

Malloy attempted to shift part of the teacher pension costs onto municipalities during the 2017 budget negotiations, a move which was met with significant pushback from municipal leaders and the public who would see their property taxes increase.

Malloy also tried to restructure the teacher pension payments the same way he restructured the SERS payments, but Nappier has warned repeatedly against such a move.

In 2008, Connecticut took out a $2 billion bond to bolster the teacher pensions system, right before the country entered a recession and the stock market plummeted.

In a March 9 letter to legislators, Nappier said any restructuring of the teacher pension debt would violate the bond covenant and be a “technical default,” harming Connecticut’s credit rating.

Nappier recommended lowering the discount rate and offered support for transferring the state’s lottery system to TERS — an idea proposed by the Commission on Fiscal Stability and Economic Growth — which she called “promising and intriguing.”

The Commission’s report also recommended moving new teachers onto a defined contribution/defined benefit hybrid plan, similar to what Michigan did to save its failing teacher pension plan.

Nappier says that after 2025, Connecticut could potentially pay off its TRS bond for a lump sum payment of $1.9 billion, potentially saving up to $260 million.

Despite the big returns generated over the past year, Nappier urged caution and “fiscal discipline” for legislators moving forward.

“Investment gains alone will not ensure the solvency of our pension funds,” Nappier said.