J-Con Woodworking, based out of Thomaston, Connecticut, opened in 1983 and quickly became a premier manufacturer of cabinets in Connecticut. Marquis (Mark) Converse and his wife Hilary ran the small shop, which employed more than a dozen people, including 8 carpenters who were part of the Local 210 Carpenters Union.

Mark originally wanted a union shop so that J-Con Inc. could do business in neighboring New York and Rhode Island. He contributed toward his employees’ pension fund with the carpenters union, along with health benefits and good pay.

Little did he know that this would ultimately destroy his business.

In 2015, J-Con’s unionized employees voted to decertify from the carpenters union. It was the second year in a row the crew of 8 had considered this option, but this year the vote was unanimous: they didn’t want to be a part of the union anymore.

Jeff Anderson, a 13-year employee of J-Con, Inc. said he and his fellow employees didn’t feel they were getting any benefit from being a part of the carpenters union.

“What we were getting, for what we were paying, we didn’t think it was fair at all,” Anderson said in an interview. “They never asked us what we wanted or what was good for us, it was just all about the money.”

The vote to decertify came with a hefty price tag — their jobs.

Following the decertification vote, the Carpenters Labor-Management Pension Fund filed suit against J-Con, Inc.

After paying into the pension fund for 30 years, J-Con was now being sued for $464,000 for its portion of the union’s underfunded pension liability. They were also sued for an additional $169,667.80 for union health benefits, even though Mark and Hilary already paid better employee benefits than the union demanded.

As it turns out, it’s not just public-sector union pension plans that are vastly underfunded.

A looming national crisis may be slowly unfolding as union pension plans across the country are in serious danger of failing, potentially cutting pension payments to retirees. This has left unions desperate, grasping for money, and pursuing damaging lawsuits against business owners like Mark and Hilary Converse.

Under the Multi-employer Pension Plans Amendment Act, signed by President Jimmy Carter in 1980, employers who are paying into a pension plan have to pay off their portion of a pension fund’s debt if they withdraw from the plan.

In the case of J-Con, Inc., that “debt” was almost half a million dollars — $58,000 per union worker employed by J-Con — even though the company had paid into the plan for 30 years and had no say in whether or not their employees voted to decertify from the union.

Unable to shoulder the cost, they were forced to lay off all their employees, liquidate the company and auction off all of its machinery to pay off loans and legal fees. “They wiped us out,” Hilary said. “We basically have nothing left.”

Part of the law dictates Mark and Hilary have to pay more than $6,000 per quarter in order to keep legal negotiations open with the pension plan. They were able to pay for three quarters before the money ran out. “We don’t know where that money went, we have no idea,” Hillary said.

The couple has tried multiple times to contact Connecticut senators and government officials to draw attention to a law they feel is unfair.

Letters to Senator Richard Blumenthal went unanswered. Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro sent a “privacy release form,” but never followed up. Senator Chris Murphy finally sent a form email after a year-long wait. Connecticut Attorney General George Jepsen’s office said it was a matter of federal law and couldn’t offer advice to private citizens.

“I feel like no one is listening to us.”

Mark Converse

Public-sector pension plans receive the most scrutiny, primarily because they are paid for with taxpayer dollars and have amassed $6 trillion in unfunded liabilities, but private pension plans run by labor unions have also amassed a large amount of debt and their futures are in jeopardy.

The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation acts as an insurer for multi-employer pensions plan, covering some of a plan’s losses if it becomes insolvent. In 2017, PBGC director Thomas Reeder testified before Congress that 187 plans were either insolvent or would fail within the next 10 years. To date, 5,000 plans have failed.

According to Reeder, PBGC’s multi-employer pension program had only $2.3 billion in assets and $67 billion in liabilities. That deficit is expected to grow to $78 billion by 2026.

In other words, the PBGC itself, which insurers these failing pension funds, is in danger of running out of money by 2025.

The PBGC only pays a limited amount when forced to cover a failing fund. For 30 years of work, a retired union member would only receive $12,000 per year through PBGC — far less than many workers were guaranteed.

None of this bodes well for dues-paying union members or the 1.5 million people receiving benefits through the PBGC. Union pension funds have already begun to cut pension payments to current retirees, most notably the Teamsters Local 707 — the highway motor freight union out of New York — whose members saw their pensions cut in half.

The U.S. Congress is currently considering a bail-out of these pension plans, a move which is supported by the American Association of Retired Persons.

J-Con, Inc’s employees were part of the Carpenters Labor-Management Pension Fund, which for several years has taken in less than it pays out. In 2015, the pension fund took in $7 million but paid out over $21 million, according to Graypools, an investors database.

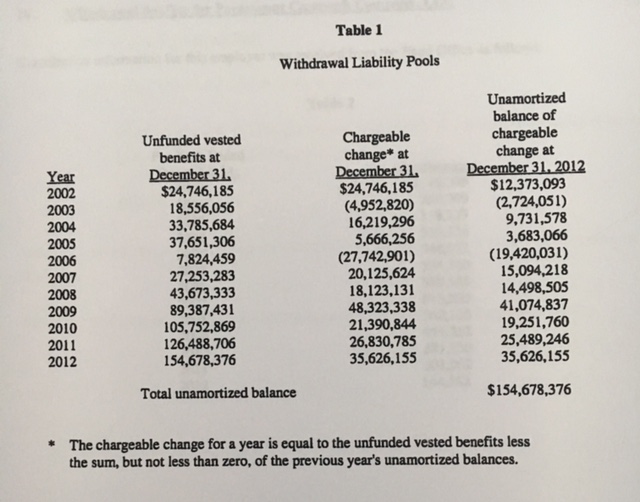

The Carpenters Labor-Management Pension Fund refused to provide Converse with their calculations. He missed filing the request during a limited legal window during which the pension fund is forced to show its math, but a 2014 lawsuit against a Rhode Island company shows the pension fund carries a hefty debt.

The Carpenters Labor-Management Pension Fund sued Paramount Restaurant Supply for $9.5 million after their subsidiary, Paramount Casework Company, LLC, went out of business in 2013.

According to court documents, the Carpenters Labor-Management Pension Fund is shown to have an unfunded pension liability of $154.6 million, amounting to more than $16,000 per participant.

So where is all the money going?

Part of the losses are due to the severe stock market downturns in 2001 and 2008, according to Joshua Gutbaum, a guest scholar at the Brookings Institute. Gutbaum testified before the U.S. Congress on the problems facing multi-employer pensions plans.

In his testimony, Gutbaum says these pension plans were hit with a “double whammy” of the economic downturns combined with pension plan “orphans.”

Orphans are those members of the pension plan whose company has gone out of business. The union member is still entitled to a pension, but there are no longer any funds coming in from an employer.

“As a result, the companies and workers still active in the plan are now left holding the [empty] bag. They are being asked to pay not only their own costs but also for the funding shortfalls of benefits to others,” Gutbaum wrote. “The result is a ‘death spiral’ under which employers that can withdraw do so and the burden on the remaining employers becomes intolerable, leading to mass withdrawal, many bankruptcies, and eventually, plan insolvency.”

Mark Johnson, Ph.D. is founder of ERISA Benefits Consulting and an expert on multi-employer pension plans. He says it isn’t just the economic downturns that have set these pension funds up for failure, but also that contributions toward the plans are declining and unable to keep up with how much the plans have to pay to retirees.

“The contribution toward the plan becomes a bargaining item in collective bargaining agreements,” Johnson said. Employers can negotiate with their unions a reduced contribution rate toward the pension plan in exchange for healthcare, wages and other collective bargaining items.

“The flaw is that they are defined benefit plans, but they are funded like defined contribution plans,” Johnson said. Because the pension is not funded based on its long-term obligations, but rather based on employees’ wages and hours of work, “there is an inherent disconnect between funding and obligations.”

“This is further complicated by the fact that employees often work for more than one employer during their careers and employers come and go out of the plan and existence,” Johnson said. “This doesn’t actually cause them to lose money, but rather to not get enough money in the first place and what they do get in contributions is subject to the market fluctuations as any other investment portfolio.”

Unfortunately for workers, that means they do not have some of the individual protections afforded by defined contribution plans and their retirement payments can be slashed as these funds dry up.

“We know that nothing is going to help us at this point. But we would like to see this law changed because its wrong. They shouldn’t be able to do this.”

Hilary Converse

It also leaves pension funds grasping at straws and looking for big cash settlements when a company either closes or, in the case of J-Con Woodworking, its employees decertify from the union. But it can be hard to collect from a small company like J-Con who can’t shoulder the burden of a half-million in unfunded liabilities.

Mark and Hilary can no longer afford their attorney and worry the pension fund may come after them personally, but say there’s nothing left for them to take. “Right now it’s in court somewhere,” Hillary said.

They are getting by brokering woodworking jobs, estimating and consulting from a small basement office, but they have neither employees nor hope of seeing a positive resolution to their situation.

Mark notes that it wasn’t just his shop and employees that were affected by J-Con closing. “It hurt our landlord, our suppliers — we had a lot of suppliers that are not getting the business anymore — it’s a huge ripple effect. Everybody lost on it.”

After J-Con was forced to close its doors, Anderson was out of work for “a couple months” before finding a new job in Danbury, leaving him with a forty-five minute commute.

“It was very tough to replace that job,” Anderson said.

Phone calls to the management company of the Carpenters Labor-Management Pension Fund were not returned.