**For full citations, charts and graphs, please download the PDF**

Executive Summary

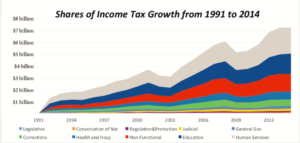

- Since 1991, the state has taken in $126 billion through the income tax.

- The top income tax rate has risen steadily since 1991 – from 4.5 percent to 6.99 percent today.

- State government spending grew 71 percent faster than inflation between 1991 and 2014.

- In the first three years after the passage of the income tax, the fastest growing area of spending was welfare, which saw a 30 percent increase over those three years. During those same years, the number of people living in poverty in Connecticut grew from 6.8 percent to 10.8 percent, which is where it stands today.

- From 1991 to today, spending on debt service payments and public employee benefits grew faster than any other category of spending. This category, called “non-functional,” grew 174 percent over the rate of inflation. The next fastest growing category, corrections, grew by 103 percent.

- The constitutional spending cap, approved by 80 percent of voters in 1992, and passed in conjunction with the income tax, was never fully implemented by state lawmakers; as a result, according to an opinion issued last year by the state’s attorney general, it is not currently in force.

Introduction

In 1991, state lawmakers asked the residents of Connecticut to support a compromise: in return for an income tax, lawmakers promised to abide by a constitutional spending cap which would, they said, ensure fiscal responsibility. But legislators failed to live up to their end of the bargain. Not only has spending risen far faster than predicted, leading to deficits followed by additional tax increases, but the spending cap was neither fully implemented – nor respected.

In the years immediately following the 1991 passage of the income tax, Connecticut lawmakers ramped up spending, favoring short-term fixes over long- term reforms. This approach has led us to the fiscal crisis Connecticut now confronts – with our state deeply indebted both to Wall Street and to retired public employees. Meanwhile, the fiscal restraint supposedly guaranteed by the spending cap never materialized.

Since the 1991 adoption of the income tax, its top marginal rate has been raised four times: in 2003, 2009, 2011 and 2015. The top rate has risen from 4.5 percent to 6.99 percent. The total cost of the income tax between 1991 and 2014 was $126 billion dollars.

As projected deficits continue to loom in 2017 and beyond, some in the legislature are already demanding another round of tax increases. Those who seek more revenue today make the same arguments as those who advocated for the income tax 25 years ago – arguing that this time the proposed new tax dollars will fix the state’s budget problems and will finally set Connecticut on the path of fiscal sustainability.

If Connecticut residents are experiencing déjà vu, it’s understandable. The proposals, justifications, and promises used today echo those made in 1991 – as well as those that have been used to justify each subsequent tax hike.

And just as the promises are the same, so will be the results: higher spending without accountability, more long term debt, and very little investment in the services that overtaxed residents should expect from their state government.

Why an income tax?

When Connecticut adopted a broad income tax 25 years ago, lawmakers traded away one of Connecticut’s chief competitive advantages compared to neighboring states. Connecticut once was the lower-tax alternative to nearby states like Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey, but in the years since the income tax was adopted, that advantage has steadily eroded.

During the 1980s, Connecticut relied on a volatile mixture of taxes to fund government. Connecticut’s corporate and capital gains tax revenue were highly dependent on favorable economic conditions, particularly the stock market’s performance. Annual revenue projections were more or less a gamble. In 1991, Connecticut’s luck finally ran out, and the state faced a large budget deficit.

To close the gap, Gov. Lowell Weicker reversed his earlier opposition to an income tax and, instead, wholeheartedly supported its imposition. Weicker and other supporters promised the income tax would end Connecticut’s deficits once and for all. Previous tax increases had been wasted on “orgies of spending,” said Weicker. But, he said, new spending controls would prevent that from happening if Connecticut adopted an income tax.

Notwithstanding Weicker’s promises, spending growth continued to outpace revenue growth in the years following the adoption of the income tax, leading to additional tax increases. Between 1991 and 2014, state spending grew 71 percent faster than inflation.

So, where did all the money go?

From 1991 to 2014, the largest area of growth was the “non-functional” part of state government. The non-functional portion of the budget includes two large costs that continue to grow to this day: (1) debt payments; and, (2) pension and health care benefits for state employees. This portion of the budget grew 174 percent over inflation, or by $34.8 billion, between 1991 and 2014.

The second fastest area of growth was corrections. This increase was due in large part to the growth in the state’s prison population in the 1990s and early 2000s. Spending in this area has slowed in recent years as the prison population has declined. Spending on corrections grew by 103 percent, or $14.2 billion, between 1991 and 2014.

Spending on welfare programs also grew dramatically, primarily due to increased spending on Aid to Families with Dependent Children and Medicaid. The cost of welfare spending grew 70 percent, or by $34 billion, between 1991 and 2014.

It’s worth noting, however, that this new spending did not lead to a decrease in statewide poverty. In fact, between 1991 and 2014, Connecticut’s poverty rate increased from 6.8 percent of the state’s population to 10.8 percent.

Taxes and Spending Before 1991

Sales Tax. Until 1993, Connecticut relied primarily on sales tax revenue to support the general fund. In the years 1985 to 1991, the sales tax, on average, accounted for half of all tax revenue. In 1991, when the income tax was implemented, the sales tax rate was cut from 8 percent to 6 percent. Subsequently, sales tax revenue fell to about 30 percent of total state revenue.

Revenue from the sales tax was extremely stable between 1985 and 2014, growing slowly and steadily, with few interruptions. There were only three periods when revenue from sales taxes decreased, excluding policy changes: the recessions of the early 1990s, the early 2000s and the late 2000s. But even at the floors of these recessions, the sales tax outperformed total tax revenue and income taxes consistently.

Capital Gains Tax. Before the 1991 income tax, the only income taxed by Connecticut was capital gains and interest. This was a much smaller tax base and far more progressive than the current income tax, relying heavily on the highest earners for revenue.

Because revenue growth was almost entirely dependent on stock market performance — which was inconsistent — revenue from the capital gains tax fluctuated wildly from year to year. Leading up to the imposition of the income tax, receipts for the capital gains tax grew by as much as 51 percent in 1984 and fell by 23 percent in 1991 (adjusting for inflation).Of the major taxes, capital gains had the highest variation in annual growth from 1980 to 1991.

Corporate Income Tax. During the 1980s, the corporate income tax accounted for a larger portion of the state budget than it has in recent budgets. At its peak in 1986, the corporate income tax accounted for 20 percent of total tax revenue. Much like the capital gains tax, corporate income tax revenue fluctuated considerably from year to year. Leading up to passage of the income tax, corporate income tax spiraled up by 27 percent in 1982 and down by the same amount in 1991.

Federal Grants. In the early and mid-1980s, federal grants, adjusted for inflation, slowly declined. This trend suddenly changed in 1987. In the years leading up to the income tax, federal grants grew dramatically, more than compensating for inflation. Between 1986 and 1991, federal grants more than doubled, rising from $784 million to $1.727 billion (in 2014 dollars). However, the year to year growth of federal grants was erratic. The state experienced its highest rate of federal grant growth in 1990 when it rose by 37 percent, slowing down to 17 percent growth in 1991. If federal grants had grown as quickly as they had the year before, the state would have received $650 million more in federal funding.

In the decade before 1991, total spending adjusted for in ation grew by an average of about 6 percent, with more growth in the latter half of the decade. The fastest area of government growth was corrections, at an average of 10 percent a year – nearly twice the rate of total spending. The Department of Correction accounted for 4 percent of total spending in 1980, but reached 6 percent in 1991.

Health and Hospitals. Health and Hospitals was the second-fastest area of government growth during the 1980s. This is a broad branch of the state government, including public health, psychiatric hospitals and treatment for addiction. At the start of the 1980s, Health and Hospitals accounted for 8 percent of general fund expenditure. The high rate of growth resulted in Health and Hospitals rising to 12 percent of spending by 1989.

Legislature. The cost of the legislature grew about 8 percent a year from 1981 to 1991; however, it was (and is) a small portion of the whole budget. In the years 1985 and 1988 to 1991, it accounted for 1 percent of total general fund expenditure. In all other years between 1980 and 2014, the legislature consumed less than 1 percent.

Taxes and Spending from 1991 to 1994

The most reliable data on the changes to the state budget brought about by the adoption of the state income tax are from the years immediately following the passage of the tax – 1991 to 1994. Many of the changes that occurred during the early years of the tax persist today.

Taxes and Volatility

In 1991, as the state dealt with the effects of a national recession, sales tax revenue fell by 6 percent, capital gains tax revenue fell by 23 percent, corporate income tax revenue fell by 27 percent, and federal grants, while still increasing, grew at half the rate of the previous year. The state projected a deficit of $1.678 billion dollars.

Of the three major sources of tax revenue, the capital gains tax was the most volatile. The annual growth of the capital gains tax between 1981 and 1991 had three times the variation of the sales tax and 20 percent more variation compared to the corporate income tax. The 1991 income tax was an attempt to address this volatility by replacing the capital gains tax with a more stable tax base.

In 1991, the sales tax reached its peak of 56 percent of total tax revenue. In the same year, the capital gains tax accounted for 11 percent of total tax revenue, meaning that the sales tax to capital gains tax ratio was 5:1.

In 1991, a at 4.5 percent income tax replaced the capital gains tax. After inflation, the net effect of this change between 1991 and 1994 was an annual total revenue increase of 25 percent, or $1.8 billion dollars in 2014 dollars. Since then, the top rate and number of brackets has increased steadily.

By 1994, the ratio of sales tax to income tax revenue had shifted to a 1:1, with each accounting for about 40 percent of tax revenue. The relative growth of the income tax would continue, reaching a 1:2 sales to income tax ratio by the early part of this decade.

Revenue from the sales tax grew steadily with few and small interruptions. Rate increases accounted for the income tax’s growing share of state revenue.

Corporate income tax receipts have declined from 1991 to 2014 as a share of overall state revenue. Policy changes caused part of the decrease, with lower rates and expanded credits. But the main driver of this change is that fewer corporations – and so less income – remain in the state to tax, as evidenced by the 17 percent decline in corporations filing to pay taxes in Connecticut between 2000 and 2014.

A Change in Spending Priorities

Education. During the 1980s, education spending grew faster than total spending, rising from 27 percent of total spending to 31 percent by 1990. Between 1991 and 1994, education funding declined, with spending down $183 million and falling to 24 percent of total spending. is was a sudden and lasting change in the state’s education spending. By 1996, education spending dropped to 23 percent of state spending,a proportion that has held fairly constant to this day.

Health and Hospitals. Between 1991 and 1994, Health and Hospitals expenditures fell by $290 million dollars, a 22 percent decline. Accordingly, the portion of the budget devoted to health and hospitals decreased from 11 percent of total spending to 8 percent. During the 2000s, there was a slight rebound, leaving this budget category at about 10 percent of total spending. However, its gains relative to other categories of spending appear to have been temporary, given its decline starting in the current decade.

Protection and Regulation. The budget category Protection and Regulation is a mix of agencies, including public safety, state police, consumer protection and other regulatory agencies. This category declined by about 12 percent between 1991 and 1994, although the decrease appears larger because some spending was shifted outside of the general fund.

Areas of Growth

Human Services. Human Services includes the Department of Social Services and programs like Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Medicaid, and the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program. During the 1980s, Human Services expenditures grew at the same rate as total spending — 5 percent — and accounted for about 25 percent of spending throughout. In 1991, this began to change rapidly. Between 1991 and 1994, spending on welfare programs grew by $1 billion dollars, a 30 percent increase. Year over year, spending on welfare grew faster than the rest of the budget, climbing to 31 percent of the budget in 1991, 36 percent in 1994 and reaching its peak of 38 percent in 1995.

Despite the significant increase in spending on welfare, however, poverty in Connecticut increased markedly from 6.8 percent of the statewide population in 1990 to 10.8 percent in 1994. Census Bureau estimates from 2014 indicate that the state’s poverty rate remains at the same level as it was in 1994.

Medicaid spending growth accounted for half the increase in Human Services spending, rising 25 percent after adjusting for inflation. In today’s dollars, that amounts to an increase of $539 million over just three years. Over the same period, health care expenditures in Connecticut grew by 15 percent, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Between 1991 and 1994, Connecticut enrolled more than 26,000 new recipients onto the cash-assistance program Aid for Dependent Families with Children, a 19 percent increase. Spending on AFDC — known today as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families — grew by $300 million (2014 dollars) and, after accounting for inflation, grew by 50 percent. After the passage of welfare reform in 1996, Human Services spending fell to 30 percent of the budget by 2001, where it has more or less remained ever since.

Corrections. In the 1980s, the fastest area of government growth was prisons, which increased by an average of 10 percent a year, nearly twice the rate of total spending. DOC accounted for 4 percent of total spending in 1980. By 1991, it had grown to 6 percent of spending. Between 1991 and 1994, total spending on corrections grew by $220 million in 2014 dollars. is trend continued until 2009, when the DOC reached its peak of 9 percent of total general fund expenditures. Since then, corrections has experienced a small decline as a percent of total spending, falling to 7 percent. is has meant a decline in actual spending. Adjusted for inflation, the reduction amounts to nearly $300 million dollars annually between 2009 and 2014.

Non-functional. The 1980s investment in prisons contributed to the state’s significant long-term liabilities. Prison guards and other state employees receive generous retirement benefits, including pensions and health care for life.

One problem with pensions and other long-term liabilities is that politicians have discretion about when they pay the bill. They can incur costs today but push off payments into the future. This allows lawmakers to take budgetary shortcuts by delaying payments. In 1991, Connecticut, like many states, wasn’t setting aside much money for its pension fund – only half of what was required to cover the real cost of the state’s promises to its workers. This caused pension costs to grow over time, both to cover the normal cost as well as to make up for past underpayments. Because of the growth in pension and retiree health care costs, the non-functional category of spending overtook prison spending in the 1990s as the fastest-growing part of the budget.

The non-functional category of state spending includes debt payments, state employee benefits and some grants to towns. Between 1991 and 1994, non- functional spending increased by 40 percent, rising to $2 billion a year in today’s dollars. By 1994, the non-functional category had reached 16 percent of spending, up from 13 percent in 1991.

This was a break in the 1980s trend. In 1981, non-functional accounted for 21 percent of total spending. Non-functional declined as a percentage of total spending over the decade, reaching a low of 12 percent in 1992. This did not reflect a decrease in actual spending during the 1980s. Rather, the category grew at a rate of almost 2 percent per year, lower than total government spending, which grew at a rate of 5 percent. As a result, the non-functional category’s share of spending decreased between 1981 and 1991.

In 1993, new income tax revenue funded a large increase in non-functional spending. The 40 percent increase in non-functional expenditure, or $571 million dollars, can explain a large share of the $1.3 billion dollar increase in spending between 1991 and 1994. The category returned to its previous high of 21 percent by 2005. In 2014, non-functional spending amounted to $4 billion or 20.4 percent of the budget.

Debt payments make up a large share of non- functional spending. According to the treasurer’s report, state bonds outstanding rose from $11 billion in 1991 to $16 billion in 1994, an increase of 42 percent. Today, the state carries more than $22 billion in bonded debt. Debt payments increased at a similar rate, costing $225 million more by 1994. The change in debt service accounts for almost half of the growth in non-functional spending.

Much of the new debt ($2.4 billion) re nanced old debt. Another $1 billion went into the unemployment insurance fund, while $777 million paid down the 1991 deficit. Half a billion went toward general projects. Less than $1 billion went to projects still standing today: $307 million for clean water projects, $289 million for school construction, $134 for housing and $111 million for transportation facilities. At the same time, infrastructure borrowing fell by $161 million.

In 1994, Payments In Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) and other local aid programs in the non-functional category cost $270 million. PILOT attempts to compensate for lost property taxes for towns hosting state buildings, nonprofit hospitals or colleges. During this period, the state also began to collect gaming revenues from newly opened casinos, which amounted to more than $100 million. This new revenue covered more than half the cost of the increased grants.

The rise in retiree benefit costs explains 10 percent of the increase in non-functional spending between 1991 and 1994. The costs of retiree health care (sometimes called “other post-employment benefits” or “OPEB”) rose by 27 percent in the same period – an increase of $27 million. Unlike state pensions, the state continues to cover retiree health care costs on a pay-as-you-go basis.

The Lasting Effects

The 11 percent increase in state spending between 1991 and 1994 was just the beginning. From 1991 to 2014, the state budget rose by 71 percent, after accounting for inflation, even as population grew a mere 9 percent. To put that in context, the cost of state government per person has risen by 42 percent over in ation since 1991, when the income tax was imposed.

Several of the shifts in spending priorities that occurred after implementation of the income tax continue to this day. Education remains at 24 percent of total spending, 7 points below its 1990 high of 31 percent. Corrections remains at 7 percent, 3 points higher than in 1980, despite crime being at historic lows.

Between the passage of the income tax and today, the largest change within the budget has been the growth in non-functional spending. Non-functional spending now consumes one- fifth of the budget, an additional 8 percent of spending. Under current policies, non-functional spending will almost certainly continue to climb, thereby crowding out essential spending on education, safety-net programs, transportation and public safety.

Although the 1991 income tax is less volatile than the capital gains tax, it nonetheless can be unpredictable during recessions and stock market downturns. As the state budget has become increasingly dependent on the income tax relative to the more stable sales tax, this instability has been magnified. During the 1980s, the capital gains tax was twice as volatile as the income tax. But the capital gains tax accounted for a mere 13 percent of tax revenue at its height in 1990. Though its variation was destabilizing, its effect was muted by its relative size. In 2014, because the income tax accounted for 54 percent of tax revenue, even moderate fluctuations cause significant disruption to the budget.

By 2002, the income tax overtook the sales tax as the primary source of state revenue. When the 2001 recession struck, revenue from the income tax fell by 14 percent, whereas sales tax revenue fell at half that rate. In 2009, the Great Recession had a similar result. In both cases, the majority of the revenue lost compared to the previous year can be attributed to the large drops in income tax revenue. The income tax’s volatility is creating the very problem it was put in place to solve.

A Path Back to Prosperity

Connecticut must change course. The Mercatus Center recently ranked Connecticut 50th for fiscal condition, just ahead of Puerto Rico. Since the adoption of the income tax, which eliminated much of Connecticut’s competitive advantage, economic performance has been lackluster.

Connecticut now has an income tax. But that doesn’t mean we must surrender ourselves to a cycle of recurring deficits and a perpetually disappointing “new economic reality.”

In order to prosper again, Connecticut needs a more competitive tax structure. at begins with fiscal responsibility, enforced by the full implementation of the constitutional spending cap. This year, lawmakers convened a commission to study definitions for the spending cap, with the goal of finally implementing this extremely popular policy. Once the commission completes its work, lawmakers should finally adopt and abide by the spending cap.

Once there are meaningful fiscal restraints in place, the focus can shift to tax reform. Connecticut should once again offer tax rates that are competitive in its region. A flatter, lower income tax would encourage more people once again to live (and pay taxes) here. The alternative — hiking tax rates further, leading to additional out-migration of people and businesses — is unsustainable at best, and at worst would lead Connecticut into fiscal insolvency.