The State of Connecticut and municipalities face a substantial burden – and now threat – from pension and retiree healthcare funds, as the stock market has plunged in recent weeks, which could leave taxpayers on the hook for higher annual payments.

Pension and retirement healthcare funds are invested in the stock market. Funding levels and annual payments are calculated based on what the state thinks are reasonable rates of return from those investments.

The lower the investment returns, the more the systems are underfunded and the higher the annual payment required to pay-off those outstanding legacy debts.

Greg Gerratana, spokesman for the Office of the State Treasurer, says that State Treasurer Shawn Wooden has taken steps to reduce stock market risk since he took over the position in January of 2019.

“The effects of the market downturn on Connecticut’s pension funds will be significant,” Gerratana said in an email. “However, the Treasurer has been positioning the portfolio more defensively and focusing on de-risking in anticipation of a potential market downturn since he assumed office in January of last year.”

The effects of the market downturn on Connecticut’s pension funds will be significant. However, the Treasurer has been positioning the portfolio more defensively and focusing on de-risking in anticipation of a potential market downturn since he assumed office in January of last year.

Greg Gerratana, spokesman for the Office of the State Treasurer

Gerratana noted the Treasurer’s Office hired a Chief Risk Officer “to monitor all risks across the portfolio.”

“We have been very focused on liquidity management, which is crucial in times of market stress, especially in the current environment,” Gerrantana said.

Between the State of Connecticut and it’s 169 municipalities, the total unfunded retirement liabilities amount to $125 billion, according to a report from the Connecticut Conference of Municipalities.

The State of Connecticut – between its retirement plans for state employees, municipal employees and teachers – is looking at a total unfunded liability between $60 and $100 billion, depending on whose report you look at and their calculated rate of return from market investments.

And that’s the catch: the actual rate of return for Connecticut’s pension funds can have a big impact.

Connecticut assumes a 6.9 percent rate of return for all its major pension plans and retiree healthcare plan, but in a year that is seeing the biggest market downturn since the recession of 2008, those returns will be a distant dream.

And that 6.9 percent rate of return is new. Connecticut assumed an 8 percent return for the State Employee Retirement System until 2017 and for the Teachers Retirement System until last year.

In 2008 and 2009, as the markets crashed, both SERS and TRS saw negative returns ranging from nearly 5 percent in 2008 to 18 percent in 2009.

Since then the state has seen a ten-year compounded annual return of roughly 8 percent for both funds, but the returns can vary. Last year, the two funds saw little more than a 3 percent return.

Mary Pat Campbell, an actuary working in Hartford and author of the blog, STUMP, which focuses on state pensions, says this year’s losses will essentially hide the state pension plans’ underlying problems.

“It’s going to look bad, but it’s going to look bad for everybody and that basically papers over the weaknesses that we had before the virus,” Campbell said. “You could have a full recovery and we’d still be in a bad position.”

It’s going to look bad, but it’s going to look bad for everybody and that basically papers over the weaknesses that we had before the virus. You could have a full recovery and we’d still be in a bad position.

Mary Pat Campbell, actuary and author of the blog STUMP

Both SERS and TRS represent two major budget problems for Connecticut, as annual payments, part of Connecticut’s fixed costs, climb higher.

Before the market downturn due to the COVID-19 virus, SERS and OPEB payments for state employees were expected to rise to $2.4 billion by 2024, and payments for teacher pensions expected to climb to $1.6 billion.

“There’s no back-stop for public pension plans other than the taxpayer,” Campbell said. “And taxpayers in Connecticut have already been stretched.”

Campbell notes that the impact on Connecticut’s annual payments will likely be stretched out over a long period of time to “smooth the experience.”

Both Gov. Dannel Malloy and Gov. Ned Lamont refinanced the pension debt for both state employees and teachers to smooth out annual payments prevent them from spiking to unsupportable levels, but they are still projected to rise to over $2 billion each in the coming decade.

The legislature approved Lamont’s refinancing of the SERS system just before the State Capitol was closed.

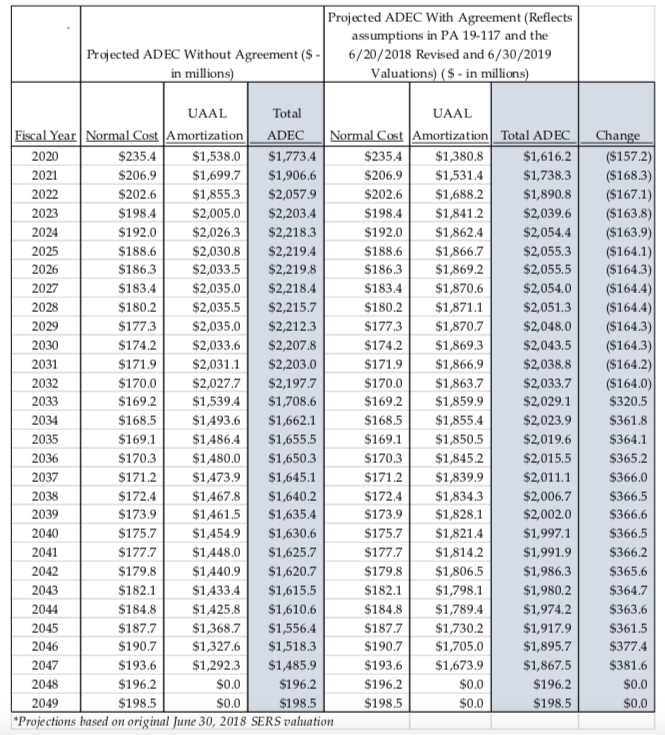

According to the Office of Fiscal Analysis, the refinancing will save the state $164.2 million per year until 2032. However, from 2032 until the end of the refinancing in 2047, the payment will be $363.9 million more than it would have been without the refinancing.

Overall, the change added $3.3 billion to the state’s payoff cost, driving it up to $50 billion, according to OFA’s analysis.

While those increasing payments definitely present a challenge for lawmakers and threaten to increase taxes to cover the payments, the market crash may throw a large wrench in the works.

“We are tops in the nation for unfunded pension and healthcare liabilities,” said Donald Klepper-Smith, chief economist for DataCore Partners LLC, and former economic advisor to Gov. M. Jodi Rell. “These unfunded liabilities stand as a huge barrier to the state’s fiscal and economic health going forward.”

Connecticut’s pension funding is one of the worst in the nation. Only Kentucky, Illinois and New Jersey are consistently ranked in worse shape than Connecticut, but the rankings vary based on assumptions.

Not only does the economic downturn hurt pension returns, it threatens to lower revenue coming into the state to make those annual payments.

“My concern is that we are locked into a state labor contract until 2027,” Smith said. “How is the state going to come up with the money to pay for lucrative contracts and benefits when the money isn’t coming in?”

Although teacher pensions can be changed legislatively, such changes generally come with a political price as teacher unions mobilize their members to speak out and pressure lawmakers who face up-coming elections.

State employee pensions, on the other hand, are set in contract between the state and the State Employee Bargaining Agent Coalition, and that contract isn’t set to expire until 2027, making any changes a matter of negotiation between the governor and unions.

How big of an effect the market downturn, the closure of businesses and the surge in unemployment will have on Connecticut’s revenue remains to be seen. The revenue decrease combined with rising fixed costs related to state bonding, pensions, retiree healthcare and Medicaid may put added pressure on the governor to bring SEBAC back to the negotiating table.

Gov. Malloy negotiated two SEBAC Concession deals in 2011 and 2017, which resulted in contract extensions, layoff protection and pay increases for state employees in exchange for higher out-of-pocket payments for employee and retiree healthcare.

Administrative changes to the retiree healthcare system have also resulted in some savings, but the cost of healthcare, on the whole, is rising.

The state also faces a projected surge in state employee retirements before July of 2022, when the annual cost-of-living increase for state pensioners is set to change and be tied to the Consumer Price Index rather than a minimum 2 percent annual COLA.

The COLA changes, however, will only affect employees retiring after July of 2022. Any employee who retires before then will still be entitled to the annual increase of at least 2 percent.

Nevertheless, the market downturn’s effect on Connecticut’s pension system will be felt by both the state and taxpayers.

“Reality is going to win the day,” Campbell said. “You don’t have the money and you don’t have the revenue coming in and it gets to the point you can’t pay the bills.”

Economists, like Smith, predict the recession could last anywhere from one year to 18 months, depending on whether or not a cure or vaccine for the virus is developed. The expected market recovery will largely depend on consumer spending, federal action and the steps taken by state governments to help keep businesses and individuals roughly whole during the downturn.

However, even during the last recovery period – ten years of a bull market – Connecticut’s pension systems just barely met their annual rate of return.

“At this point, there isn’t a current estimate for the total losses to be experienced in the capital markets,” Gerratana said. “But we have a fully diversified portfolio that is designed to weather the storm and eventually take advantage of investment opportunities as the markets improve.”

Lisa Kessler

April 29, 2020 @ 2:19 pm

I am planning to retire in June of 2026, at the age of 65.7 years. I have taught in the city of Hartford since 1988. I’m concerned that the state will not be able to honor the assurances of paying pensions to retired teachers like me.

If the state declares bankruptcy at some point, what does that do to it’s financial obligations, like pension payments to retirees?